The Cost That’s Never Counted

It’s hard enough counting the stuff you can see.

And you’d think it’d be damn near impossible to count the stuff you can’t see.

But that’s not so.

Nineteenth-century French economist Frédéric Bastiat, as imagined in Midjourney

Nineteenth-century French economist Frédéric Bastiat, as imagined in Midjourney

With a bit of elbow grease and forethought, you can calculate the accounting (seen) cost of a particular action and the economic (seen and unseen) cost of that action.

This is one of the most important skills you can develop. If you’re a parent, this is the one skill that, if your child learns it, will almost guarantee a high minimum level of success in life.

I’m talking about the ability to calculate opportunity cost.

What is Opportunity Cost?

Opportunity cost is an economic concept that refers to the potential benefits an individual, investor, or business forgoes when choosing one alternative over another.

In simpler terms, it’s what you give up to do something else.

This idea is crucial because it helps people understand the actual cost of their decisions, not just in terms of money but also in terms of forgone opportunities.

Here are three examples of opportunity cost:

- Investing in Stocks vs. Holding Cash: If you decide to invest $1,000 in the stock market instead of keeping it in a savings account, the opportunity cost is the interest you would have earned on that $1,000. On the flip side, if the stocks do well, the opportunity cost of not investing could be the gains you missed.

- Going Back to School: If you choose to return to school full-time, the opportunity cost includes the salary you’re not earning by working during that time and any career advancement opportunities you might miss.

- Spending Time: If you spend the evening working on a project instead of going out with friends, the opportunity cost is the enjoyment and relaxation you would have experienced during the night out.

Opportunity cost is about trade-offs. It helps you make more informed decisions by allowing you to consider what you’re potentially giving up.

If you’re struggling with grasping the concept, let my French friend Freddy help.

The Broken Window Fallacy

The Broken Window Fallacy is a concept introduced by the 19th-century French economist Frédéric Bastiat, illustrated in his essay “Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas” (“What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen”).

The fallacy begins with a scenario where a vandal breaks a shopkeeper’s window. Some people (perhaps Paul Krugman) argue that the broken window has a silver lining because it generates business for the glazier (the window repairer), who will presumably spend his earnings elsewhere, thus stimulating the economy.

However, Bastiat points out that this viewpoint is myopic because it considers only the immediate effects (what is seen) and ignores the broader implications (what is not seen).

The shopkeeper must spend money repairing the window instead of on other goods or services that the shopkeeper might have preferred, such as buying new stock, investing in another project, or saving for future needs.

The economy hasn’t gained a new window; it merely replaced one already there.

The real cost includes the opportunities foregone due to the money spent on repair rather than on something else.

The relation to opportunity cost is direct and profound. In the Broken Window Fallacy, the opportunity cost is what the shopkeeper sacrifices as a result of the window being broken. It’s the value of the opportunities lost—the goods or services the shopkeeper cannot now purchase or invest in because the money had to be used to fix the window.

Bastiat uses this parable to illustrate a broader economic principle: true costs consider both the seen and the unseen, including what has been foregone or sacrificed. This underscores the importance of looking beyond immediate, visible effects to consider what other opportunities could have been pursued with the same resources.

In summary, the Broken Window Fallacy cautions against the notion that economic activity alone (like fixing a window) is a sign of economic health. It emphasizes understanding opportunity costs and recognizing that resources spent in one area are resources that cannot be spent elsewhere, highlighting the importance of considering the full range of economic consequences of any action or policy.

If you’re a parent or grandparent, let’s take the argument to the kids.

The Stanford Marshmallow Experiment

The Stanford Marshmallow Experiment is a famous psychological study by psychologist Walter Mischel at Stanford University in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The experiment focused on delayed gratification, or the ability to wait to obtain something one wants.

In the study, a child was offered a choice between one small reward (a marshmallow) provided immediately or two small rewards (two marshmallows) if they could wait for about 15 minutes, during which the experimenter left the room and then returned.

The study observed how long each child could resist the temptation of the immediate reward and wait for the larger, delayed reward. Follow-up studies also examined how the children’s ability to delay gratification correlated with their future success in various areas of life, such as academic achievement, health, and personal finances.

Relating this to opportunity cost, the marshmallow experiment illuminates the concept regarding self-control and evaluating future benefits versus immediate satisfaction. The opportunity cost of choosing the immediate marshmallow is the extra marshmallow that could have been obtained by waiting.

The children who waited effectively decided that the opportunity cost of the immediate gratification was too high compared to the potential future reward.

This experiment illustrates a broader principle in economics and psychology: individuals often face choices that involve trading off immediate benefits for greater long-term gains. The ability to evaluate and act in favor of long-term rewards, despite the opportunity cost of forgoing immediate gratification, is a crucial aspect of decision-making and significantly impacts life outcomes.

Now that we’re on a first-name basis with opportunity cost let me tell you about my X experience.

Ze Germans on X

I came across this tweet on Wednesday:

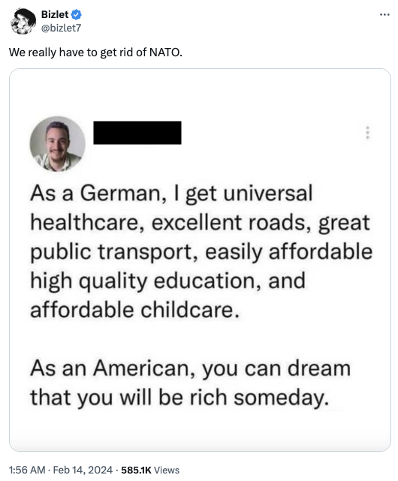

Credit: @bizlet7

I cracked up. I’m sure that tweet was made up, but nevertheless, I was in stitches.

But it illustrates opportunity cost at the national level perfectly.

For Germany, allegedly, they’ve got all these nice things. (Many Germans on the thread complained about their suboptimal healthcare and late Deutsche Bahn trains.) But let’s suppose all this is true.

What has Germany given up for this?

Essentially, it has given up its sovereignty, safety, and control by being a US vassal. That’s the unseen. The counterargument is that it gained the “world’s greatest military” as its ally (the seen).

For the US, it’s got Germany under its thumb (the seen). But what could the USG have spent that money on (the unseen)? Hospitals? Libraries? Giving your money back to you?

Wrap Up

Opportunity costs are everywhere and occur every day in your life.

Calculating them over time will help you and yours make better decisions. If only our politicians did the same.

Bastiat once wrote, “The real cost of the State is the prosperity we do not see, the jobs that don’t exist, the technologies to which we do not have access, the businesses that do not come into existence, and the bright future that is stolen from us. The State has looted us just as surely as a robber who enters our home at night and steals all that we love.”

That puts things in perspective.

Comments: