How to Deal with Crash Uncertainty

LONDON — A reader writes in raising a very good point.

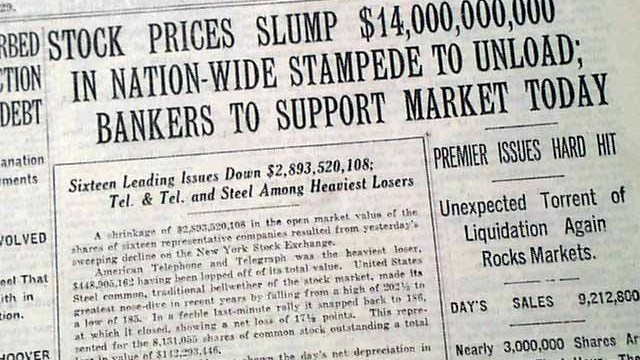

Like many of us he’s concerned about a possible financial crash.

The problem is no one can say when such a crash will occur. OK, plenty of people can and will say, but no one actually knows.

Having the humility to accept we can’t know when disaster will strike is the first step towards preparing for it properly. I’ll explain what I mean by this in a moment.

First, let’s consider a challenge we all face when it comes to weighing up the threat of a crisis.

“It is too expensive to withdraw totally from the market,” this reader says, “as it could be years before a crash occurs.”

I agree.

In fact, I’d go further. For sake of argument, let’s say you were to liquidate all your equity positions. Not only would you incur transaction costs and and likely trigger a tax event, you could miss out on further pre-crash upside.

It’s tricky. The only solution that would remove all uncertainty would be to know precisely when the next crash will be. And that’s impossible.

So instead, we must accept uncertainty and prepare accordingly.

Here’s a nice extract from Jim Rickards’ book The Big Drop that applies to this discussion:

When you have a problem in the intelligence world, invariably it’s what mathematicians call “undetermined”. That’s just a fancy way of saying you don’t have enough information.

If you had enough information to solve the problem, a high school kid could do it. The reason it’s a very hard problem to solve is because you don’t have enough information.

What do you do when you don’t have enough information? Well, you can throw up your hands – that’s not a good approach. You can guess – also not a good approach. Or you can start to fill in the blanks and connect the dots.

You’re still not sure how it’s going to turn out but you can come up with three or four different scenarios. In all probability the problem is going to come out one of several ways.

Jim goes on to explain how to check you’re looking at sensible scenarios and how to monitor them on an ongoing basis.

A quick aside. I was talking to someone in our industry, a publisher (not mine, I hasten to add!), about the importance of investing with alternative scenarios in mind.

“I hate that!” he said.

His objection was based on the notion that an editor should have a clear, opinionated world view.

While that’s great for selling newsletters, it’s not the best way to run your money. You can make a killing going all-in on a particular view of how things will pan out. You can also go broke.

Jim’s scenario-based approach is a sensible, grown-up way to tackle the problem of uncertainty. It was a big reason why I agreed to get involved with Jim’s Strategic Intelligencehere in the U.K..

Another important fact to take on board is that a financial crisis – even a really, really bad one – is not the same as the world coming to an end.

There will be a world after the next crisis, whenever that crisis happens to come. Some will come out better than where they started. Some will be battered and bruised, but still standing.

Sadly, some will lose everything.

Your objective is not to be in that final group.

If you think a crisis lies ahead (and historically, there’s never been a time when one hasn’t occurred, sooner or later), it makes sense to keep some cash on hand for new investments.

Why?

Because there tend to be more bargains around after a crash.

In my view there’s a lack of value in the markets right now. However that doesn’t equate to there being no opportunities out there.

My American colleague Chris Mayer has become obsessed by a project of his that looks at so-called 100-baggers – stocks that deliver 100 times on an initial investment.

He looked into companies that have performed the trick over the last forty years. I saw him speak about this in Baltimore last month, and something stuck with me.

The right time to buy into these companies had little to do with wider market sentiment. You could have found great investments at times when the broader market was overvalued, undervalued, or doing little of interest either way.

The lesson? Always be looking.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that throughout history there have been investors who have sat tight during periods of extreme market turbulence.

It’s not easy to do, and it doesn’t always pay off.

But if you can afford to, and you have the patience, trusting that the market will still be there when the storm has passed can often be a smart course of (in)action.

Of course, it’s easier to sit tight if you didn’t go all-in in the first place.

The reader I quote above has the right idea.

“In a nutshell I propose to think twice before buying a new stock,” he writes.

“I will console myself with the thought that in the event of a major crash we will probably have more to worry about than the price of stocks and given time the market will reassert itself.”

To summarize, then:

- Uncertainty is a fact of life. No one can know precisely when the next crisis will happen.

- The time to prepare is now – but don’t put all your chips on one outcome. Uncertainty is a fact of life.

- There will be a world after the next crisis.

- Always be looking for opportunities. While you wait for catastrophe, others are making money. Just don’t put all your chips on one idea.

Until next time,

Ben Traynor

for The Daily Reckoning, U.K.

P.S. Be sure to sign up for The Daily Reckoning — a free and entertaining look at the world of finance and politics from every possible angle. The articles you find here on our website are only a snippet of what you receive in The Daily Reckoning email edition.Click here now to sign up for FREE to see what you’re missing.

Comments: