My Conversation With Ben Bernanke

Editor’s Note: Jim Rickards has published a third book entitled “The Big Drop: How to Grow Your Wealth During the Coming Collapse.” It’s available exclusively for readers of his monthly investment letter called Strategic Intelligence. Before you read today’s essay, please click here to see why it’s the resource every investor should have if they’re concerned about the future of the dollar.]

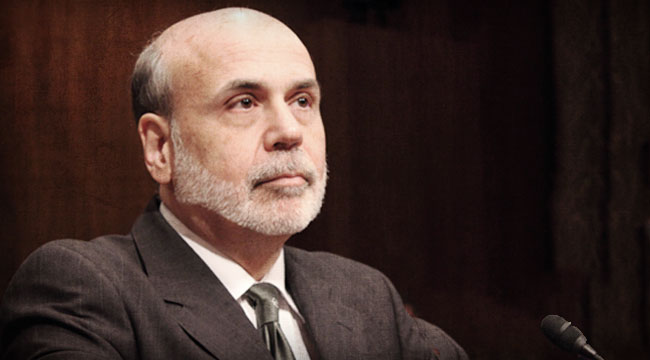

On May 27, I had the privilege of spending time with Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the Federal Reserve System, in Seoul, South Korea. We were both there as keynote speakers at an international financial forum sponsored by the leading business publication in Korea.

The theme of the conference was currency wars and their impact on Korea. Our audience was interested in how monetary policy and exchange rate fluctuations affected Korea versus its trading partners and competitors, especially China, Japan and Taiwan.

Above all, the audience wanted to learn how Fed policy on interest rates would affect the dollar, and what impact policy would have on developed economies and emerging markets.

In addition to the formal presentations, our event sponsors organized a small VIP reception that included Bernanke and me along with the CEOs of the Korea stock exchange, the Korea Banking Institute, the Korea Federation of Banks and the Korea Financial Investment Association.

There were about 10 of us in all representing the financial elites of Korea and some distinguished scholars and economists from Japan; Bernanke and I were the only Americans. The setting was private and allowed us ample time for one-on-one discussions before the main conference commenced.

My conversation with Bernanke began casually enough. In the early 2000s, I had helped to establish the Center for Financial Economics at Johns Hopkins University. The center had selected its director from among the senior monetary economists at the Federal Reserve.

Not long after bringing our director on board, Bernanke tapped him to return to the Fed to serve as special adviser for communications, the person responsible for crafting announcements of Federal Open Market Committee actions that Wall Street economists slavishly dissect after each FOMC meeting for clues about interest rate policy changes.

I chided Bernanke for “picking off” our director. He laughed and said, “We didn’t pick you off, we just borrowed him; we gave him back,” which was true enough. Our director had just returned to the center after two years at the Fed. That was a good icebreaker to turn the conversation to more serious matters.

I had a copy of Bernanke’s book, Essays on the Great Depression (2000), which contains much of the research on which he built his academic reputation. Bernanke had shown that gold was not a constraint on money supply creation during the Great Depression, contrary to what many economists and analysts take for granted.

From 1929-1933, money supply was capped at 250% of the market value of gold held by the U.S. government. The actual money supply never exceeded 100% of the value of the gold. This meant that the Fed could have more than doubled the money supply without violating the gold constraint.

The implication is that policy failure during the Great Depression was caused by the Fed’s discretionary monetary policy, and not gold.

I told Bernanke that I had used his research in my own work on gold in my book, Currency Wars (2011). When I offered my interpretation of his work, he replied, “That’s right.”

This confirmation was ironic because the Fed is facing the same challenges today in increasing bank lending and money velocity as it did in the Great Depression.

Gold is not even part of the system today. Bernanke may have identified the money velocity problem in his book, but as chairman, he had no greater success in solving it than his predecessors.

Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke warmly inscribed my copy of his book Essays on the Great Depression (2000). It includes research that shows gold did not constrain money supply growth during the Great Depression, contrary to what many analysts assert.

Following this introduction, Bernanke then made a set of remarks that I found both surprising in their candor and refreshing in the extent to which he was willing to take issue with some of what his successor, Janet Yellen, has said recently on the subject of Fed interest rate hikes.

Yellen gave a speech just prior to my meeting with Bernanke in which she said, “I think it will be appropriate at some point this year to take the initial step to raise the federal funds rate.”

In contrast, Bernanke told me, “The interest rate increase, when it comes, is good news, because it means the U.S. economy is growing strongly enough to bear the costs of higher rates without slowing growth.” Unlike Yellen, Bernanke did not tie himself to a particular month or year. He explicitly said the rate hike would come in an environment of strong growth.

Today the U.S. economy is close to negative growth and is nowhere near the kind of robust growth that Bernanke associated with a rate increase. The clear implication is that the Fed will be in no position to raise rates anytime soon.

Bernanke also warned that the rate increase had to be clearly communicated and anticipated by the markets. He said, “Markets are not as deep and liquid as they were before the crisis.”

The suggestion was that market expectations and Fed actions need to be aligned in order to raise rates without a market crash. He expressed the hope that “The rate increase may be an anticlimax because the markets anticipate it.”

That makes sense. The problem is that right now markets anticipate the first fed funds rate increase in early 2016, not in 2015. Bernanke’s warning about illiquidity and hope for an anticlimactic market reaction are further evidence that he does not see a rate hike coming before 2016, at the earliest.

Turning to the international monetary system, Bernanke was also candid and said, “The international monetary system is not coherent.” He explained that the current combination of floating exchange rates, fixed exchange rates and moving pegs means that trading partners have no confidence in their relative terms of trade and this acts as a drag on trade, foreign direct investment and capital expenditures.

He said, “Over time, it would be important for the countries of the world to talk more about how to avoid the mixture of fixed and floating exchange rates. We need new ‘rules of the game.’”

Of course, international monetary experts know that the phrase “rules of the game” is code for a reformation of the international monetary system, or what some call a global reset. Bernanke was explicit that this reset is needed to end the dysfunction of the current system.

Some aspects of a global reset have already been put in place. For the past several years, the IMF has been attempting to change its quota system to give China more votes at the IMF, more in line with China’s 10% share of global GDP. Right now China has less than 5% of the votes, which is low compared with some much smaller economies in Europe.

The U.S. Congress has refused to approve legislation needed to implement the changes at the IMF. Referring to the closed-door negotiations among the U.S., IMF and China that led to the proposed reset in the quotas, Bernanke said, “I participated in this.”

This was surprising to me because traditionally matters involving the IMF are handled by the Treasury Department rather than the Federal Reserve. Bernanke’s confirmation of his participation made it clear that the Fed, Treasury, IMF and China are working hand in glove on the early stages of the reset.

China has grown increasingly frustrated at the delays from Washington in changing the IMF quotas to give China a larger vote. The Chinese have begun building their own version of the IMF in the form of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and other institutions through the BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Bernanke was dismissive of the AIIB and said, “I don’t think it’s going to be very important. It’s going to be a footnote.” I took this to mean that Bernanke expects the IMF voting reforms to move forward, in which case, China will be happy to play by the rules of the existing Bretton Woods institutions rather than try to start its own club independent of the IMF.

This interpretation is consistent with China’s large gold acquisitions in recent years. The U.S. has about 8,000 tons of gold, the eurozone has about 10,000 tons, and the IMF has about 3,000 tons. China would need at least 4,000 tons, probably more, to be a credible member of this elite group.

The AIIB is best seen as a kind of head fake, and Bernanke implicitly confirmed this. China’s real goal is to acquire gold, have the yuan included in the IMF’s special drawing rights basket and have its IMF votes increased. All of these resets are now well underway.

Bernanke next discussed whether the stock market was in a bubble. In typical Fed style, he said, “It’s very difficult to know.” He also seemed relaxed about a sudden market correction.

He said, “What if the stock market dropped 10% or 15%? What difference does it make? Is there anything that looks like a systemic risk? I don’t see that right now, I don’t see anything that looks like a threat.”

In other words, the Fed’s job is to protect the system as a whole, not to protect investors from sudden drops in stock values. Bernanke could be wrong about a bubble. He certainly missed the mortgage market bubble in 2007 and the systemic risk that emerged in 2008. Whether he’s right or wrong about bubbles, he clearly said he’s not concerned about a 3,000-point drop in the Dow Jones index. Investors are on their own when it comes to that.

Finally, in discussing his legacy as Fed chair, Bernanke turned back to his research on the Great Depression, where our conversation began.

He said the three lessons of the Great Depression were that the Federal Reserve needed to perform as a lender of last resort, increase the money supply when needed and be willing to “experiment” in the style of FDR.

Bernanke defined “experiment” as being willing to do “whatever it takes” to head off deflation and depression. In summing up his own performance, he said, “We tried to do whatever it took. We don’t know yet what the long-term implications are.” His forecast was that “the Fed will be more proactive in the future.”

My impression was that Bernanke knows the jury is still out on his tenure as Fed chairman. There is no doubt that his actions in 2008 and 2009 prevented a worse result at the time. But they may have produced a more dangerous condition today.

There was good justification for QE1 in 2008 and 2009 as an emergency liquidity response to a global financial panic. This is consistent with the Fed’s role as lender of last resort, as Bernanke said.

But QE2 and QE3 were not in response to any liquidity crisis. They were in the category of “experiments,” as Bernanke defined them. Experiments are fine in the laboratory but much riskier in the real world. Experiments are a good way to advance science, but every scientist knows that most experiments fail to produce expected results.

Ben Bernanke was generous with his time and candid in his remarks. Still, I was left with an unsettling feeling that he knew that QE2 and QE3 were failed experiments, despite his public defense of them. Growth in the U.S. has been anemic for six years, and there is good evidence that we are sliding into a new recession.

The Fed can’t cut rates now, because they failed to raise them when they had the chance in 2010 and 2011. Markets are probably in bubble territory, which means they could easily fall 30-50%.

The Fed will not act during the first 15% of a market crash, because they will see it as a normal correction, not a bursting bubble. By the time the Fed is ready to act, it will be too late, just as it was in 2008.

The collapse momentum will feed on itself in ways the Fed cannot control. Bernanke may have learned some lessons from the Great Depression, but it seems he has not learned the lessons of the Panic of 2008.

Regards,

Jim Rickards

for TheDaily Reckoning

Photo credit: Medill DC, Flickr

P.S. If you haven’t heard, I’ve just released a new book called The Big Drop. It wasn’t a book I was intending to write. But it warns of a few critical dangers that every American should begin preparing for right now.

Here’s the catch — this book is not available for sale. Not anywhere in the world. Not online through Amazon. And not in any brick-and-mortar bookstore.

Instead, I’m on a nationwide campaign to spread the book far and wide… for FREE. Because every American deserves to know the truth about the imminent dangers facing their wealth.

That’s why I’ve gone ahead and reserved a free copy of my new book in your name. It’s on hold, waiting for your response. I just need your permission (and a valid U.S. postal address) to drop it in the mail.

Click here to fill out your address and contact info. If you accept the terms, the book will arrive at your doorstep in the next few weeks.

Comments: