Financialization = Ruin

The United States economy is largely a “financialized” economy.

Financialization: “The increase in size and importance of a country’s financial sector relative to its overall economy.”

Is financialization a sickness of corroding empires? Do previous examples exist?

These are the questions we tackle today.

The financial industry represented 10% of the gross domestic product in 1970.

By 2010 the financial system ballooned to 20% of the gross domestic product… inflated by the helium of artificially depressed interest rates.

A financialized economy demands perpetually expanding credit — that is, debt — to keep the show going.

That debt becomes a millstone set upon society’s neck.

It chokes off savings and investment in productive assets.

Speculation goes amok.

The Great Divergence

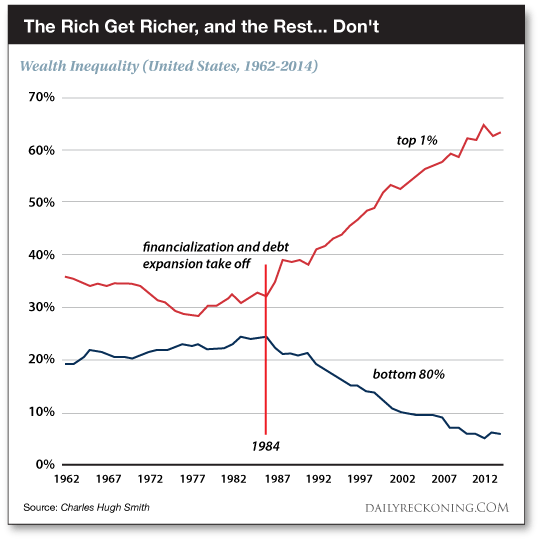

Meantime, wages wallow — and the middling classes with them. The great chasm began to open in the mid-1980s:

Is this not the United States economy? We believe — to vast extent — that it is the United States economy.

Yet does history reveal parallel examples?

A finance man named Johnston — Henry Johnston — stretched the historical canvas upon his work desk. He gave it a good looking-over.

His conclusion:

An examination of history reveals recurrent instances of financialization that bear remarkable similarities, which invites the conclusion that perhaps the predicament in the American economy in recent decades is not unique and that the ever-rising power of Wall Street was in a sense preordained.

Proceed, sir — you have seized our attention.

The U.S. Has Done Well by Doing Good

It is in this context that it pays to revisit the work of the Italian political economist and historian of global capitalism Giovanni Arrighi (1937–2009)… [he] explored the origins and evolution of capitalist systems dating back to the Renaissance and showed how recurrent phases of financial expansion and collapse underpin broader geopolitical reconfigurations.

Occupying a central place in his theory is the notion that the cycle of rise and fall of each successive hegemon terminates in a crisis of financialization. It is this phase of financialization that facilitates the shift to the next hegemon.

The United States is the contemporary hegemon.

It has constructed a global order that in theory butters the world’s bread — but in reality butters its own parsnips:

Observers of the current American hegemony will recognize the transformation of the global system to suit American interests. The maintenance of an ideologically charged “rules-based” order — ostensibly for the benefit of everyone — fits neatly into the category of conflation of national and international interests…

The period of ascendency is based on an expansion of trade and production. But this phase eventually reaches maturity, at which point it becomes more difficult to profitably reinvest capital in further expansion.

In other words, the economic endeavors that propelled the rising power to its perch become increasingly less profitable as competition intensifies and, in many cases, much of the real economy is lost to the periphery, where wages are lower. Rising administrative expenses and the cost of maintaining an ever-expanding military also contribute to this.

“Much of the real economy is lost to the periphery, where wages are lower”?

“Rising administrative expenses and the cost of maintaining an ever-expanding military?”

Only a dull, dull blade could fail to notice the American condition in these words.

The “Signal Crisis”

Does the United States presently confront a “signal crisis,” Mr. Johnston? What is one?

This leads to the onset of what Arrighi calls a “signal crisis,” meaning an economic crisis that signals the shift from accumulation by material expansion to accumulation by financial expansion. What ensues is a phase characterized by financial intermediation and speculation.

Another way to think about this is that having lost the actual basis for its economic prosperity, a nation turns to finance as the final economic field in which hegemony can be sustained. The phase of financialization is thus characterized by an exaggerated emphasis on financial markets and the finance sector.

Yet the transformation from productive phase to financialized phase is temporarily gorgeous.

It attains — in fact — the appearance of an economic renaissance.

It is mistaken for the triumphant phoenix, rising gloriously from flames…

An “Illusory Respite From the Trajectory of Decline”

Mr. Johnston:

The corrosive nature of financialization is not immediately evident — in fact, quite the opposite. Arrighi demonstrates how the turn to financialization, which is initially quite lucrative, can provide a temporary and illusory respite from the trajectory of decline, thus deferring the onset of the terminal crisis.

Here he cites the British example:

For example, the incumbent hegemon at the time, Great Britain, was the country hardest hit by the so-called Long Depression of 1873–1896, a prolonged period of malaise that saw Britain’s industrial growth decelerate and its economic standing diminished. Arrighi identifies this as the “signal crisis” — the point in the cycle where productive vigor is lost and financialization sets in.

And yet:

As Arrighi quotes David Landes’ 1969 book The Unbound Prometheus, “as if by magic, the wheel turned.” In the last years of the century, business suddenly improved and profits rose. “Confidence returned — not the spotty, evanescent confidence of the brief booms that had punctuated the gloom of the preceding decades, but a general euphoria such as had not prevailed since… the early 1870s… In all of Western Europe, these years live on in memory as the good old days — the Edwardian era, la belle epoque.”

Industrial supremacy yielded to the gimcrack, cheapjack and ruin-racked deceptions of financialization.

All was illusion.

A Perfect Parallel

Meantime:

As surplus capital moved out of trade and production, British real wages began a decline starting after the mid-1890s — a reversal of the trend of the past five decades.

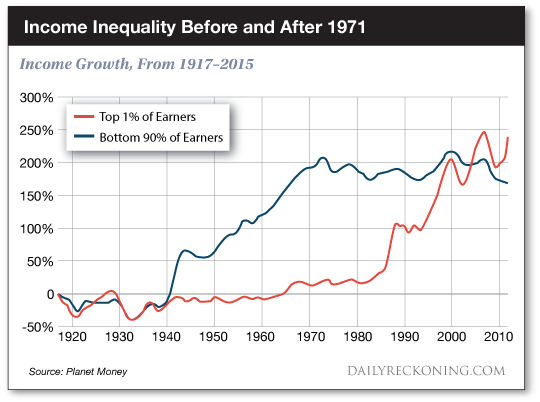

We refer you to the following image.

It reveals that the bottom 90% of American earners advanced steadily from the early 1940s through the early 1970s.

It further reveals that the tiptop 1% of earners lost ground to the bottom 90% across the same stretch.

Yet in the early 1980s the tiptop 1% went leaping ahead… and began showing society their dust:

As with British labor in the 1870s… so with American labor since the 1980s… both unfortunates of financialization.

“Essentially,” Johnston continues:

By embracing financialization, Britain played the last card it had to stave off its imperial decline. Beyond that lay the ruin of World War I and the subsequent instability of the interwar period, a manifestation of what Arrighi calls “systemic chaos” — a phenomenon that becomes particularly visible during signal crises and terminal crises.

The U.S. Embraced the British Model

As Great Britain seized hold of financialization to brace its eroding imperial pillars, so the United States has seized hold of financialization to brace its eroding imperial pillars:

The process of financialization emerging from a signal crisis was repeated with startling similarities in the case of Britain’s successor, the U.S. The 1970s was a decade of deep crisis for the U.S., with high levels of inflation, a weakening dollar after the 1971 abandonment of gold convertibility and, perhaps most importantly, a loss of competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing.

With rising powers such as Germany, Japan and, later, China able to outcompete it in terms of production, the U.S. reached the same tipping point and, like its predecessors, it turned to financialization. The 1970s was, in the words of historian Judith Stein,the “pivotal decade” that “sealed a society-wide transition from industry to finance, factory floor to trading floor.”

And as Great Britain’s 19th-century financialization yielded a brilliant yet false prosperity, America’s 20th- and 21st-century financialization has worked the identical effects:

This, Arrighi explains, allowed the U.S. to attract massive amounts of capital and move toward a model of deficit financing — an increasing indebtedness of the U.S. economy and state to the rest of the world.

But financialization also allowed the U.S. to reflate its economic and political power in the world, particularly as the dollar was ensconced as the global reserve currency. This reprieve gave the U.S. the illusion of prosperity of the late 1980s and ’90s, when, as Arrighi says “there was this idea that the United States had ‘come back.’”

Had the United States truly come back? Or did it simply enjoy a temporary and illusory bounce — a mere feint?

Borrowed Time

More:

Financialization merely stalls the inevitable and this has only been laid bare by subsequent events in the U.S. By the late 1990s, the financialization itself was beginning to malfunction, starting with the Asia crisis of 1997 and subsequent popping of the dot-com bubble, and continuing with a reduction in interest rates that would inflate the housing bubble that detonated so spectacularly in 2008.

Since then, the cascade of imbalances in the financial system has only accelerated and it has only been through a combination of increasingly desperate financial legerdemain — inflating one bubble after another — and outright coercion that has allowed the U.S. to extend its hegemony even a bit longer beyond its time.

Mr. Johnston concludes with a piece co-authored by this Arrighi character and scholar Beverly Silver:

The expansion can be expected to be a temporary phenomenon that will end more or less catastrophically… But the blindness that led the ruling groups of [hegemonic states of the past] to mistake the ‘autumn’ for a new ‘spring’ of their power meant that the end came sooner and more catastrophically than it might otherwise have… A similar blindness is evident today.”

A similar blindness is indeed evident today.

A fellow need be blind to be blinded from the blindness.

And only the blind cannot see that all of Washington is blind…

Comments: