The “Ghetto-izing” of America

Consider the defining characteristics of a ghetto:

1. The residents can’t afford to live elsewhere.

2. Everything is a rip-off because options are limited and retailers/service providers know residents have no other choice or must go to extraordinary effort to get better quality or a lower price.

3. Nothing works correctly or efficiently. Things break down and aren’t fixed properly. Maintenance is poor to non-existent. Any service requires standing in line or being on hold.

4. Local governance is corrupt and/or incompetent. Residents are viewed as a reliable “vote farm” for the incumbents, even though whatever little they accomplish for the residents doesn’t reduce the sources of immiseration.

5. The locale is unsafe. Cars are routinely broken into, there are security bars over windows and gates to entrances, everything not chained down is stolen — and even what is chained down is stolen.

6. There are few viable businesses and numerous empty storefronts.

7. The built environment is ugly: strip malls, used car lots, etc. There are few safe public spaces or parks that are well maintained and inviting.

8. Most of the commerce is corporate-owned outlets; the money doesn’t stay in the community.

9. Public transport is minimal and constantly being degraded.

10. They get you coming and going: Whatever is available is double in cost, effort and time. Very little is convenient or easy. Services are faraway.

11. Residents pay high rates of interest on debt.

12. There are few sources of healthy real food. The residents are unhealthy and self-medicate with a panoply of addictions to alcohol, meds, painkillers, gambling, social media, gaming, celebrity worship, etc.

13. Nobody in authority really cares what the residents experience, as they know the residents are atomized and ground down, incapable of cooperating in an organized fashion, and therefore powerless.

I submit that these defining characteristics of ghettos apply to wide swaths of American life. Ghettos are not limited to urban zones; suburbs and rural locales can qualify as well.

The defining zeitgeist of a ghetto is the residents are effectively held hostage by limited options and high costs: public and private-sector monopolies that provide poor quality at high prices.

Daily life is a grind of long waits/commutes, low-quality goods and services, shadow work (work we have to do that we’re not paid for that was once done as part of the service we pay for) and unhealthy addictions to distractions and whatever offers a temporary escape from the grind.

We’ve habituated to being corralled into the immiseration of limited options and high costs; the immiseration and sordid degradation have been normalized into “everyday life.”

We’ve lost track of what’s been lost to erosion and decay. We sense what’s been lost but feel powerless to reverse it. This is the essence of the ghetto-ization of daily life.

Behind the facade of normalization, even high-income lifestyles have been ghetto-ized. But saying this is anathema: Either be upbeat, optimistic and positive or remain silent.

What’s worse, the ghetto-ization or our inability to recognize it and discuss it openly?

Below, I show you how two dominant economic trends of the past 50 years are reversing. What are they? And why does it matter? Reason.

Will Class Identity Finally Matter Again?

By Charles Hugh Smith

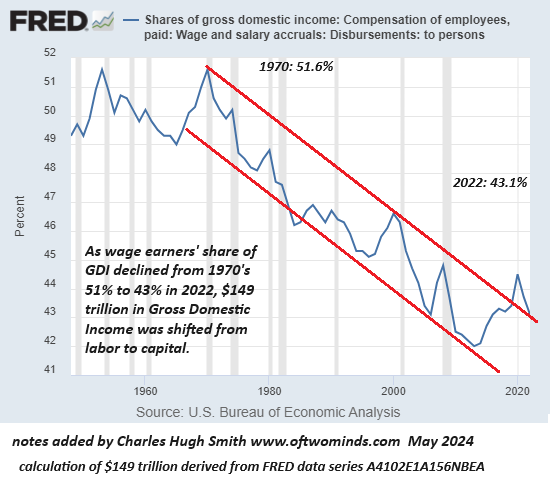

Two primary trends may be reversing: wage earners — labor — may be finally starting to regain some of the share of gross domestic income (GDI) lost to capital over the past 54 years, and economic class identity that collapsed in favor of individual identity — enabling the siphoning of $149 trillion in GDI from labor to capital since 1970 — may be reviving.

The two trends are intertwined: the cultural dominance of identity politics came at the expense of economic class identity, which effectively blinded us as a nation to the multi-decade transfer of wealth from wage earners to owners/managers of capital.

If we’re wondering how the bottom 90% have lost ground, we can start with the social-cultural blindness to the collapse of class identity which enabled the dominance of capital politically, economically and socially, as manifested in the rise of globalization and financialization, the tools used to transfer income from labor to capital.

Capital’s increasing share of domestic income was not pre-ordained; it was the result of specific policy decisions, starting with globalization’s downward pressure on domestic wages. The fancy term for forcing American workers to compete with other workers around the world whose cost of living is a fraction of ours is global wage arbitrage: capital shifted jobs to low-wage regions at will to increase profits at the expense of domestic wages.

This is the fundamental advantage capital has over labor: Capital is globally mobile, labor is grounded in a particular place. Yes, workers can move around the world, too, but there are restrictions, both legal and in cost/sacrifice, as the effort and expense required to move from one country to another are significant.

Capital doesn’t care about a place or community; that’s up to the residents. If capital shifts overseas to lower costs/increase profits, well, folks, make do with what’s left.

Financialization amplified capital’s dominance of the economy, for capital gained tremendous power as credit and leverage expanded capital’s scale and reach at the expense of domestic workers and communities.

It’s equally important to note that the corporate dominance generated by globalization and financialization also gutted small business and the local enterprises that provide the bulk of the jobs and cohesion in communities.

The RAND study Trends in Income From 1975 to 2018 concluded that capital skimmed $50 trillion from labor from 1975–2018. Using data from the Federal Reserve’s FRED database (series A4102E1A156NBEA), correspondent Alain M. calculated the actual sum for the period 1970–2022 (2022 being the most recent data available) was a staggering $149 trillion.

If wage earners’ share of gross domestic income had remained at 51% instead of declining to 43%, wage earners would have received an additional $149 trillion over those 52 years. That’s roughly $3 trillion a year, which works out to an additional $22,000 annually for America’s 134 million full-time workers or an additional $18,000 annually for the nation’s entire workforce (full-time, part-time, self-employed, gig workers) of 163 million.

No wonder the purchasing power of a day’s work has declined to the point many cannot afford to buy a home or start a family or rent an apartment.

Time magazine published a gloves-off summary of the RAND study in September 2020: The Top 1% of Americans Have Taken $50 Trillion From the Bottom 90% — And That’s Made the U.S. Less Secure.

Consider these excerpts from the article:

There are some who blame the current plight of working Americans on structural changes in the underlying economy — on automation, and especially on globalization. According to this popular narrative, the lower wages of the past 40 years were the unfortunate but necessary price of keeping American businesses competitive in an increasingly cutthroat global market. But in fact, the $50 trillion transfer of wealth the RAND report documents has occurred entirely within the American economy, not between it and its trading partners. No, this upward redistribution of income, wealth and power wasn’t inevitable; it was a choice — a direct result of the trickle-down policies we chose to implement since 1975.

We chose to cut taxes on billionaires and to deregulate the financial industry. We chose to allow CEOs to manipulate share prices through stock buybacks, and to lavishly reward themselves with the proceeds. We chose to permit giant corporations, through mergers and acquisitions, to accumulate the vast monopoly power necessary to dictate both prices charged and wages paid. We chose to erode the minimum wage and the overtime threshold and the bargaining power of labor. For four decades, we chose to elect political leaders who put the material interests of the rich and powerful above those of the American people.

That this level of incendiary outrage has seeped into the mainstream media tells us that the bill for America’s gluttony of inequality is long overdue.

The pendulum reached an extreme and is now starting to swing back, as evidenced by previously anti-union work forces (VW auto workers, for example) starting to vote in favor of unionization. Trillion-dollar cartels/monopolies — the golden children of capital — are finally facing some pushback from their work forces and antitrust agencies.

Here is the Federal Reserve chart of wage earners’ share of gross domestic income:

Note the basic structure of lower highs and lower lows: Labor’s share of GDI recovers a bit of ground in “good times” — speculative bubbles and massive federal stimulus — and then reverts to trend once the bubbles pop.

The substitution of identity politics for economic class identity has been catastrophic for the bottom 90% of the American workforce and the bottom 90% of American households. Capital can buy political influence to obtain policies that favor capital; the workforce has no power other than the cohesion generated by shared identity manifested in cooperative action in pursuit of economic shared interests.

Corporate apologists and PR flacks like to demonize labor organizations as “Marxist” to misdirect us from the reality that labor organizations are necessary counterweights to corporate dominance.

Once the counterweights have been stripped out, the system decays to what we have today: a hyper-globalized, hyper-financialized corporatocracy with zero interest in anything beyond maximizing private gains by whatever means are available (cough, doing God’s work, Pelosi portfolio, cough). The net result is a failed state geared to serve the interests of the few at the expense of the many.

A pendulum can only reach so far before it reverses and proceeds to the opposite extreme (minus a bit due to friction). Labor, capital and class identity are all starting to swing away from 50-year-plus extremes that decimated the financial security and share of domestic income of the bottom 90%.

It’s long overdue.

Comments: