Your Punishment From Daddy Fed

Happy Thursday from sunny Sicily!

It’s been blazing brightness all week here on the Mediterranean’s largest island. We’ve had a great time so far.

But I’m so sunburnt, it’s great to be inside typing away.

When I started writing the Rude Awakening two years ago, we had far fewer readers than we do now. We also have a different interest rate environment.

So I thought I’d revisit a piece I wrote when rates were on the floor and I was begging Jay Powell to raise them.

But does the Fed only manipulate rates? Or is it manipulating you? You may not be so surprised to hear the answers to those questions.

Quick Warm-Up

Everything I write in today’s essay you already know subconsciously. Some of you may have studied economics and consciously understand it.

Personally, I love economics — especially the microeconomics of the Austrian School — because it’s inherently inborn knowledge pulled to the front of one’s mind.

It’s almost as if you’ve always known it, but were never aware of it. The enormous benefit of becoming aware of it is that you can wield it to your advantage.

I’m going to walk you through, step-by-step, my ideas of what’s going on today. I didn’t originate any of this. It’s knowledge people brighter than I have discovered, but I’ve been lucky enough to come into contact with and piece together.

Time Preference

I want it all,

I want it all,

I want it all,

and I want it now.– Queen

Queen guitarist and astrophysicist (really) Brian May wrote this song. Apparently, his wife, Anita Dobson, an English television actress, inspired him by constantly saying, “I want it all, and I want it now.”

That’s a believable explanation for any married man.

Everyone wants more satisfaction rather than less. And we want that satisfaction earlier rather than later.

That’s the practical way to think about “time preference.”

We know big goals take more time to accomplish. If we’re willing to invest more time to achieve these goals, we’re demonstrating a low time preference. Someone who wants their flatscreen TV and new car RIGHT NOW reveals a high time preference.

(Sometimes, the terminology gets confusing. Just remember, Lower time preference means Longer. Lower, longer. Lower, longer. Now, you’ve got it.)

So why does time preference matter?

It matters because people who save and invest, rather than consume, build civilization. To forgo your immediate desires to build resources for increased future consumption is how we move forward as a civilization.

Prudence. Long-term planning.

Ah, the days of yesteryear.

We can thank our lately besmirched forefathers for setting up all this for us. If they didn’t save and invest, putting off consumption until later, we’d still be hunting every day for food. (The enviroMENTALists overtly desire this with gardening rather than hunting.)

Essentially, our civilization is not the privileges our forefathers bequeathed us so much as the consumption they forewent. Frederic Bastiat distinguished between the seen and unseen. I encourage you to do the same.

And that leads us to our next step: marginal utility.

Marginal Utility

Understanding this concept changed my life. It changed the way I view objects, people, and goals.

“Utility” in economics means pleasure or satisfaction, not “usefulness.” “Marginal” means “additional.”

When economics professors teach this, they go for cardinal numbers (the number of units at a price level). And if you’re Apple, you can indeed gauge demand for, say, iPhones. But ordinary people have neither the resources nor the know-how to do that.

So for us, thinking of utility in an ordinal way makes much more sense.

That is, we just list out our preferences in order from most desirable to least desirable.

For instance, our list at this moment may look like this:

- Eat a good breakfast.

- Talk to the boss about a promotion.

- Pick up kids at 3pm from school.

- Move into a McMansion.

You may look at this list and say, “Geez, surely the promotion isn’t more important than picking up the kids!” Or “Why is having a good breakfast even on this list?”

Both are good questions. But this is my list, not yours.

And that’s the beauty of economics. Understand that every one of us has different ways of thinking about our priorities.

Why does my list look like this?

Perhaps I forgot to pick up my son last time and he thinks I don’t love him as much as I used to. Or I need a good breakfast because my health isn’t that great. My promotion matters, for sure, and I need that first before I move into my McMansion.

Crucially, this list may change in the next 5 seconds. Things come up all the time.

Of course, actual time matters as well. I have to pick up my kids at 3pm. That’s when they get out of school. I have no choice there.

But I’ve been working for years on my promotion, so I think the time to talk about it is today. But I’ve got leeway if my desire to talk about my promotion may not be high on my boss’s marginal utility list.

OK, say I ate a good breakfast. Yum! My list now looks like this:

- Talk to the boss about a promotion.

- Pick up kids at 3pm from school.

- Move into a McMansion.

Now, I just talked to my boss about my promotion. It’s not happening. Ugh. Here’s my new list:

- Pout and surf the net all day at work because I’m pissed off.

- Pick up kids at 3pm from school.

- Look for a new job.

- Tell my wife the McMansion is on hold.

- Check my wife’s phone to make sure she hasn’t signed up for a dating site.

See? The list radically changed.

The Powers That Be (TPTB) know this. They mess with it all day, every day. There are two primary ways for them to do this: monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Monetary policy has been king for quite a while, so let’s show how artificially lowering interest rates distorts incentives.

How Artificially Low Rates Leads to Malinvestments

It’s 2008. The stock markets follow real estate and credit markets down the toilet. The Fed (duh! duh! daaaa!) shows up in a red cape to save the day. It lowers interest rates to zero. We’re thrilled they “stepped in” to “rescue” the economy.

The markets rally. We feel better.

But what really happened there?

What The Fed did was mess up everyone’s incentives. By lowering interest rates, they reduced the discount on all future cash flows in the economy.

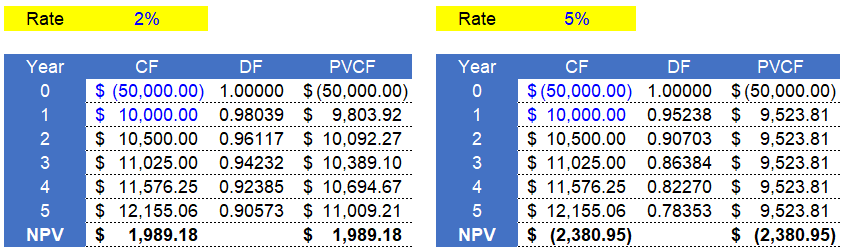

Take a look at these tables. They are the same project. The only difference is the rate at which we discount the future cash flows is lower in the left table.

I’ll walk you through it…

When it comes to project finance or financial modeling, we use the NPV method. NPV stands for net present value. Essentially, we estimate all the cash flows of a project and its interest rate. Then we discount all the cash flows by that rate back to the present.

If the NPV is positive, we accept the project. If it’s negative, we reject it.

So let’s look at our project with two different discount rates.

First, we have an initial investment, or outflow, of $50,000. The next five years’ cash flows are all positive: $10,000, $10,500, $11,025, $11,576.25, and $12,155.06, respectively. The DF column represents the discount factor applied to each cash flow. That formula is 1/(1+r)^t. So for Year 1, at a 2% discount rate, the discount factor is 1/(1+0.02)^1, or 0.98039. The present value of that future cash flow (PVCF) is $10,000 x 0.98039 = $9,803.92.

We apply that formula to each cash flow.

If the project has a 2% interest rate or cost of capital, the net present value (NPV) is a positive $1,989.18. As the NPV is positive, we would take on the project. That is, we’d spend the $50,000 and start the work.

But notice the NPV when rates are at 5%.

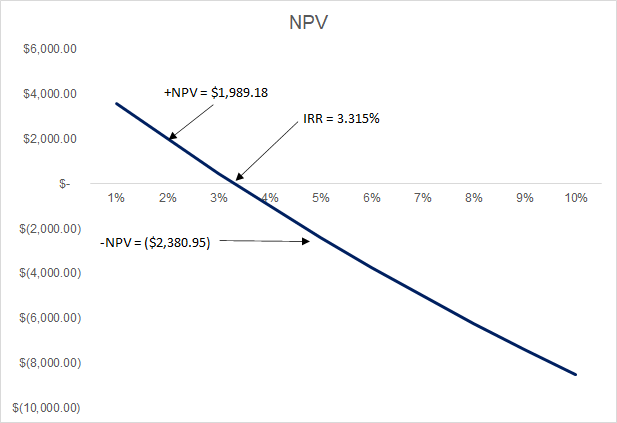

We’d reject this project outright, even though it has the same cash flows. In fact, we’d reject this project for any rate above 3.315%, the project’s internal rate of return (IRR). That means rates must be pretty darn low to make this project attractive to investors.

Here’s the project at various discount rates:

Now imagine this happening for millions of projects around the world. That’s the power central banks wield. We’re not exaggerating when we say they alter incentives worldwide.

Projects that are marginally profitable at lower interest rates would be woefully unprofitable at historically normal rates like 5%.

At a more retail level, think how much more likely one is to buy that flatscreen TV on credit at zero interest rates, rather than, say, 5%. Because you can’t earn any money at all in your savings account anymore. This has huge repercussions for society.

It may be the main reason why women have given up traditional values and are turning to making money in more… unsavory ways. It’s why many men have given up on ever owning a home or getting married. It also explains the rampant gambling in the stock market via RobinHood and in the cryptocurrency markets.

Why not, right? It’s just too hard to do things the old-fashioned way.

Economists blame women’s literacy rates for the decrease in birth rates. What if we suppose it’s not reading, but mathematics skills that lower birth rates? After all, if a woman knows she and her husband can’t support a kid, why would they have one? Everything is more expensive when rates are on the floor.

To sum it up, central banks incentivize companies to create malinvestments by artificially lowering rates. This makes projects look more profitable than they actually are once rates get back to normal.

Congratulations, you’ve just quantified time preference!

What About Now?

Of course, now we live in a world where interest rates are above 5%. Using what we learned above, what do you think the Fed’s trying to do?

Yes, you’ve got it! The Fed is trying to get you to stop spending money by making questionable projects unprofitable. Financing flatscreen televisions, cars or any other consumption items is what Jay Powell is trying to stop.

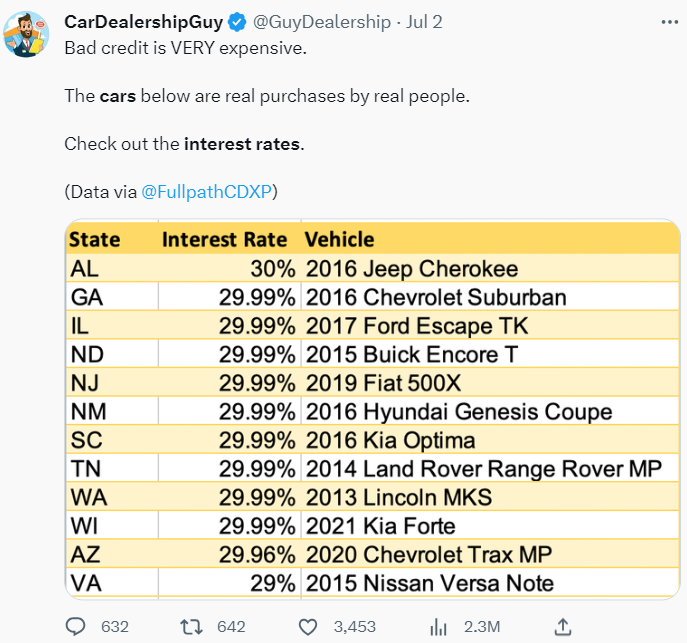

Look at what’s happened to people with bad credit trying to buy a car:

Credit: @GuyDealership

You’ve got people paying up to 30% interest on their purchases. A 2021 Kia Forte’s MSRP is roughly $20,000. 30% of $20,000 is $6,000. That’s now a $26,000 car.

This is punishment by Daddy Fed to get you to stop spending and slow the rate of inflation.

To Wrap It Up

Central banks bring investments forward in time that may not have happened at all. And perhaps should not have happened at all.

And now you know why we’ve been messed about since 2008.

Now we’re dealing with a slowing economy because the Fed realized its error and started to hike in 2022. It’s getting expensive to finance purchases.

Understanding time preference, marginal utility and how central banks manipulate our preferences with rates equips you with the skills you need to navigate any Fed cycle.

Many of you seemed to enjoy my Thursday economics lessons. Let me know if these topics are something you’d like me to continue, or if you have any questions, just drop me a line here.

For now, I wish you a wonderful rest of your week!

Comments: