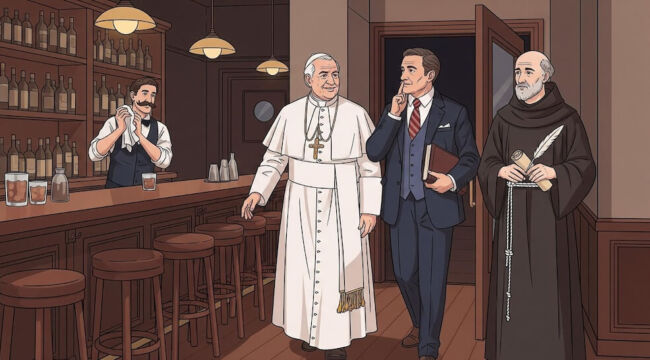

The Pope, the Libertarian, and the Angelic Doctor Walk Into a Bar…

My good friend and host of the No Way Out podcast, Mark McGrath, likes to call me the second-most famous Villanova graduate in Italy. Of course, the most famous one sits on the Throne of St. Peter and has this uncanny penchant for pissing me off.

I had high hopes for Papa Leone, as we call him here in Italy. But time and again, from blessing ice blocks to condemning nation-states for enforcing borders, he’s let me down.

He only slightly pulled back recently about the border issue, saying:

States have the right & duty to protect their borders, but this should be balanced by the moral obligation to provide refuge. With the abuse of vulnerable migrants, we are not witnessing the legitimate exercise of national sovereignty, but rather serious crimes committed or tolerated by the state. Increasingly inhumane measures are being taken—even politically celebrated—to treat these ‘undesirables’ as if they were garbage and not human beings.

This is a man who majored in mathematics and spent his entire adult life traveling the world as a priest. Was I wrong? Did I need to re-examine my views?

Maybe. So here’s what I’ve come up with.

Western immigration policy isn’t really about immigration. It’s about what you believe a society is.

Is it a universal moral community? A collection of private property holders who set their own boundaries? Or a hierarchy of obligations where love expands outward, but not blindly?

Three very different thinkers — the aforementioned Pope Leo XIV, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, and Thomas Aquinas — have become touchstones in the West’s immigration brawl. And they offer three radically different answers to the question that keeps politicians, bishops, and citizens shouting past each other:

Who owes what to whom?

Let’s take a quick tour through the theological, libertarian, and classical-philosophical frameworks shaping the West’s most explosive policy fight.

Pope Leo XIV: “I Was a Stranger and You Welcomed Me”

Pope Leo’s immigration theology is simple: If you’re a Christian, you don’t get to dodge Matthew 25:35-40.

35 For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, 36 I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me.’ 37 Then the righteous will answer him, saying, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? 38 And when did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? 39 And when did we see you sick or in prison and visit you?’ 40 And the King will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’

He doesn’t talk about “flows,” “net migration,” or “refugee intake ratios.” He talks about Christ showing up at your door in need.

Of course, Jesus didn’t say, “Welcome me and fifty million other people, empty your treasury, and destroy your culture in the process.” Important.

But to Papa Leone, every migrant — the persecuted, the displaced, the starving — carries the face of Jesus. Hospitality isn’t philanthropy. It’s an obligation. A spiritual duty. A test of Christian witness.

If Pentecost shattered linguistic and ethnic barriers, then the Church cannot advocate rebuilding them for the sake of policy convenience.

This does not mean “abolish the borders.”

But it does mean refugees must be given refuge, the vulnerable must be protected, and nations must put human dignity first — even when it’s inconvenient.

To the Pope, Western societies don’t merely choose whether to welcome the desperate. Their credibility as moral actors depends on it. He suggests every time the West slams the door, it erodes the Christian foundations the West claims to defend.

This worldview produces universalist, humanitarian-leaning policies — and no small amount of friction with nationalist politics on both sides of the Atlantic.

Hans-Hermann Hoppe: Borders Are Property Lines

If Pope Leo is preaching universal love, Hans-Hermann Hoppe is loading the libertarian shotgun and bolting the gate.

Hoppe’s worldview is the polar opposite: Immigration is not a moral drama — it’s a property rights question.

He argues that what we call “open borders” is actually forced integration, because governments decide who gets to enter and settle in a territory that doesn’t belong to them. In Hoppe’s ideal world, migration is purely voluntary: you arrive only if a property owner explicitly invites you. No invitation, no entry.

Everything else, in his view, is coercion.

That leads to a very different policy picture:

Strong borders are strictly enforced. There’s no welfare for newcomers and, ideally, no welfare at all. Private invitation, not public law, controls migration. Finally, there’s no tolerance for government-mandated integration programs.

Critics say Hoppe ignores desperation, global inequality, and the interconnected nature of economies. Hoppe says he’s simply defending the right to say “no.”

Hoppe also notes democratic rulers don’t care about immigration the way the populace does (bolds mine):

As far as emigration policy is concerned, this implies that for a democratic ruler, it makes little, if any, difference whether productive or unproductive people, geniuses or bums leave the country. They all have one equal vote. In fact, democratic rulers might well be more concerned about the loss of a bum than that of a productive genius. While the loss of the latter would obviously lower the capital value of the country and loss of the former might actually increase it, a democratic ruler does not own the country. In the short run, which is of the most interest to a democratic ruler, the bum, voting most likely in favor of egalitarian measures, might be more valuable than the productive genius who, as egalitarianism’s prime victim, will more likely vote against the democratic ruler. For the same reason, quite unlike a king, a democratic ruler undertakes little to actively expel those people whose presence within the country constitutes a negative externality (human trash which drives individual property values down). In fact, such negative externalities – unproductive parasites, bums, and criminals – are likely to be his most reliable supporters.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Thomas Aquinas: Charity, Yes — But Ordered Charity

And then there’s Thomas Aquinas, offering something everyone in this debate seems to have forgotten: nuance.

As JD Vance rightly noted, Aquinas’ ordo amoris — “the order of love” — argues that love must be universal andrightly ordered. You owe more to those closest to you, but not exclusively so. You protect your family before strangers, your community before outsiders… unless a stranger’s need is so urgent that your circle must widen.

For Aquinas, moral judgment depends on circumstances, prudence, and proportion.

It’s not “open borders.” It’s not “fortress nation.” It’s a structured hierarchy of obligations:

- First, your kin

- Then your neighbors

- Then your countrymen

- And then, when need demands, the stranger

That said, Aquinas opposed granting immigrants immediate rights. From Summa Theologica (I-II, Q. 105, A. 3):

If foreigners were allowed to meddle with the affairs of a nation as soon as they settled down in its midst, many dangers might occur, since the foreigners, not yet having the common good firmly at heart, might attempt something hurtful to the people.

Aquinas insists charity is expansive — but never unthinking. It stretches outward, but not without discernment.

Policy-wise, this would entail robust but carefully managed asylum systems, prioritization of genuine, urgent needs, integration that strengthens, not destabilizes, communities, and a willingness to help — paired with the prudence to know when and how.

If Pope Leo offers the moral ideal and Hoppe the libertarian veto, Aquinas provides a framework for balancing compassion with coherence.

Three Visions, Three Wests

You can map most Western debates over immigration to these three worldviews.

The Catholic universalists argue from dignity and solidarity.

The restrictionists argue from property, sovereignty, and social cohesion.

The classical Thomists argue from prudence — a middle path that avoids the absolutism of both extremes.

Here’s the tension:

Pope Leo’s view risks moral overextension and political backlash.

Hoppe’s view risks shrinking society into a collection of gated fiefdoms.

Aquinas’ view demands judgment — the one thing modern politics hates most.

And because the West is spiritually fractured, economically strained, and demographically anxious, these frameworks now collide daily in legislatures, churches, and households.

Wrap Up

Immigration is a moral referendum on what Western societies believe about community, obligation (and its limits), the dignity of the outsider, the rights of the insider, and the scope of compassion in an age of scarcity.

Pope Leo says our first duty is to Christ in the migrant.

Hoppe says our first duty is to protect free association and private property.

Aquinas says our first duty is ordered love — beginning at home, radiating outward, never forgetting the stranger, but never dissolving the bonds that hold a community together.

Three visions. Three Wests. One crisis with no easy answers.

The immigration debate is ultimately a debate about the soul of the West. And the West hasn’t yet decided which of these three voices it wants guiding its conscience.

Comments: