Oil Is Back

In 45 years, the world has gone from energy shortage and fears of “Peak Oil” to an energy glut where it seems the world is drowning in oil and floating on a cloud of natural gas at the same time.

Yet that may not last. My models predict a long-term rise in energy demand and energy prices.

Of course, the same amount of energy has always been around. It’s just a question of technology, geopolitics and price as to whether the energy gets to where it’s needed when it’s needed.

Hydraulic fracturing, so-called “fracking,” is the biggest single factor in opening up oil supplies in the past 30 years. Oil that was always around but trapped in certain rock formations can now be released when those formations are subject to high pressure by pumping in water and sand composites.

Other innovations include horizontal as opposed to vertical drilling, so that one well can extract oil from a much larger area than before. Another rapidly growing aspect of the energy industry is the deployment of large liquefied natural gas (LNG) vessels than can move LNG across oceans instead of the gas being confined to continental areas.

Developing economies with large energy reserves such as Saudi Arabia and Russia are motivated to maintain output at high levels in order to finance ambitious internal development budgets, social spending or simple corruption. Russia and Saudi Arabia have been leaders in capping oil output lately.

But how long will that last with the U.S. picking up the slack, becoming a major energy export powerhouse? The race is on for global market share.

These technological and political drivers have caused much lower energy prices in recent years. Does this mean that energy companies are doomed to decades of low prices?

The answer may surprise you. I recently plugged into a private presentation by the top executives of a major energy company. Following is what they’re telling their investors behind closed doors:

With the energy business, it’s always best to take a long view, 20 years or more. That’s because the costs and scale of infrastructure are so large that overinvestment or underinvestment based on temporary trends can put a company out of business.

The bottom line is that based on the best information available now, executives forecast that the U.S. role as a major oil and gas exporter will not only persist, but expand greatly.

The constraint on short-term growth is not the energy or technology available but the infrastructure needed to move the oil and natural gas to the ports. These executives also take the view that the world will need every possible source of energy that can be developed to meet the increase in global demand projected for the next several decades. Here are the actual notes from the closed-door meeting:

Just a 1–2% change in the supply/demand equation for oil can move the price by $40 per barrel or more. Right now supply and demand are more balanced, restoring the price back to one where most can operate at a profit at this time. OPEC and Russia are helping keep global supply and demand fairly well in balance.

The CEO presented an analysis that projects demand for oil and gas to grow by 40% over the next 20 years despite an increase in renewable energy sources and even assuming conventional combustion engine cars obtain a fleet average of 50 mpg.

Electric cars are not expected to have a major impact in the next 20 years although they will grow substantially in number. Fossil fuels are expected to remain at around 80% of energy supply, as they are now, for most of this time period even as renewable sources do grow over time.

Global demand is expected to come from China, India, other parts of Asia and Africa during the next 20 years, while demand may actually drop in the U.S. and the EU. But those drops would be dwarfed by the increased demand from the other parts of the developing world.

The CEO expects the U.S. will become a substantial exporter of LNG eventually, once the infrastructure exists for that to happen.

A long-term imbalance creating a potential shortage of oil to meet daily demand is more likely than an oversupply in this view. It is also advisable to avoid shale plays, because they deplete so quickly. Companies should prefer long-lived reserves that others have abandoned.

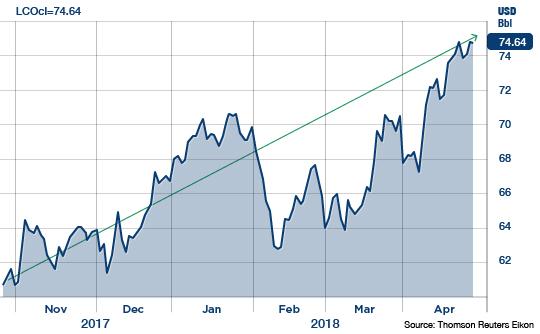

As shown in the chart below, oil has staged a spectacular 25% rally from $60 per barrel in October 2017 to $70 per barrel today. The question is whether this rally represents supply shortages, robust demand by end-users or dollar debasement by inflation.

My models show that demand for energy from oil and natural gas will remain robust for decades to come.

With this long-term demand for energy as a backdrop, what are our predictive analytic models telling us about the prospects for the prices of energy and stocks of companies that support the energy sector in the months ahead?

Right now, my analysis agrees with the aforementioned CEO that demand for oil and gas combined will grow 40% over the next 20 years despite the increase in renewable energy sources, even assuming conventional combustion engine cars achieve a fleet average of 50 miles per gallon.

The demand for natural gas alone will increase 100% over the next 20 years.

These are the most conservative demand assumptions produced by our models and they assume a much higher shift to renewable energy and electric cars than standard models. In other words, these demand figures assume the electric car and solar revolutions will succeed and not fail. But we’re still going to use massive amounts of fossil fuels even with the success of renewables.

The world will need this energy not because of static demand in the U.S., Japan and Europe but because of exploding demand from China, Africa, South America and South Asia. Natural gas is expected to have the biggest increase in demand of any single source of energy during the next 20 years including wind, solar and electric vehicles.

If electric vehicles, solar and wind do not live up to their potentials, the demand for oil and natural gas will be even greater. In that situation, you could see an energy shortfall equivalent to 6 million barrels per day.

This shortfall could arise if electric vehicles fail to meet a target of 190 million vehicles by 2040 or if conventional internal-combustion engines fail to achieve the 50 mile per gallon fleet goal.

Apart from these natural and technical considerations, we cannot forget the role of geopolitics.

Venezuela is imploding and is coming close to the status of a failed state like Somalia or Yemen. If Venezuela collapses entirely, its energy output will come offline unless the U.S. intervenes militarily or unless China creates a cordoned-off energy mini-state on Venezuelan soil. Either scenario is certain to push up prices and restrict output under the best of circumstances.

Finally, we have learned through investment banking channels that China is tipping its hand with regard to the Saudi efforts to conduct a public offering of Aramco, the world’s largest oil company.

Aramco officials are balking at some of the disclosure and regulatory requirements that come with a public offering. They may pursue a private placement whereby China, or perhaps Russia, buys a direct stake. This gives Saudi Arabia the cash they need but still satisfies Aramco’s desire for nondisclosure.

China would not be pursuing this costly path if they did not see the same long-term supply shortages that my models predict.

I’ll be keeping a very close eye on this space in the days ahead.

Regards,

Jim Rickards

for The Daily Reckoning

Comments: