Just War? Or Just More War?

There was a time when nations at least pretended to seek moral clarity before marching to war. Today, with the drums pounding louder for a U.S. confrontation with Iran, I’m wondering if anyone in Washington even remembers — or ever learned — the Catholic Church’s “just war” doctrine.

Because if they had, they’d know we’re nowhere near satisfying it.

The Original Red Line

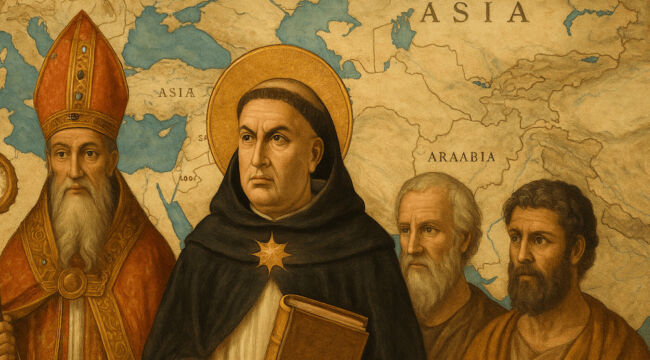

The idea that war can be morally justified — and not just a tragic necessity—goes back nearly 1,700 years. The Catholic doctrine of bellum iustum (“just war”) was never a blank check to bomb whoever you like. Instead, it was a stringent framework. A checklist, if you will, of moral prerequisites. And it began with a Roman lawyer who became a bishop…

St. Augustine: War as a Lesser Evil

Augustine of Hippo (354–430) is often regarded as the father of just war theory. Writing in the collapse of the Roman world, he argued that war is not inherently evil, but the motives and methods can be.

He laid down the foundational principles:

- Legitimate Authority: Only duly constituted public authorities may wage war.

- Just Cause: War must confront a real and certain danger (not preemptive vibes).

- Right Intention: The ultimate goal must be peace, not conquest, punishment, or (ahem…) oil.

He wasn’t giving Rome a moral out. He was trying to limit war to cases of absolute necessity. War wasn’t noble — it was regrettable, and only to be used in defense of justice.

St. Thomas Aquinas: Sharpening the Sword Carefully

If Augustine provided the spiritual rationale for war in extreme circumstances, Thomas Aquinas — the 13th-century Dominican friar and intellectual heavyweight — gave the Church its legalistic and moral scaffolding.

Writing during the High Middle Ages, in a world of Crusades, knightly orders, and theocratic kings, Aquinas was no idealist. He lived in a Christendom that waged war regularly. But instead of blessing every campaign with holy water, he used reason and Scripture to limit war’s use and scope.

In his Summa Theologiae (Secunda Secundae, Q. 40), Aquinas posed a pointed question: “Is it always sinful to wage war?”

His answer was “no”—but with serious caveats.

Aquinas’ Core Criteria for a Just War:

He distilled Augustine’s broad principles into three precise conditions:

- Proper Authority – Only a legitimate ruler or government can declare war. That means no freelance crusaders, vigilante coalitions, or defense contractors with lobbyists at the Pentagon. You need sovereign legitimacy, not just money or ambition.

- Just Cause – Those attacked must deserve it for a wrong they’ve done. Not for having a different religion. Not for being strategically annoying. And certainly not for sitting on oil or rare earth minerals. Aquinas argued that war must be defensive, or a response to a prior injustice.

- Right Intention – The goal must be peace, not glory or loot. This is the most subtle and most violated rule today. Wars fought for political popularity, campaign donations, or regional dominance — common incentives in D.C. — flunk this test miserably.

These weren’t abstract ideas for Aquinas. He was engaged in the debates of his time, including the moral limits of the Crusades and the rights of pagan nations. His writings would later shape both Catholic and secular law on a wide range of topics, from sovereignty to international conflict.

Modern Additions Built on Aquinas’ Frame

Subsequent theologians and moral philosophers extended his logic, building what’s now called “jus ad bellum”(justice before going to war):

- Last Resort – You must try everything else before using force. That means sanctions, negotiations, mediation — even patience.

- Probability of Success – If a war is likely to fail or spark a broader catastrophe, it cannot be justified.

- Proportionality – The expected benefits must outweigh the damage inflicted.

- Discrimination – Civilians are not combatants. Targeting or disregarding them is always unjust.

None of these contradict Aquinas — they complete him.

The Modern Magisterium: Popes Say No (A Lot)

In recent history, Popes have leaned heavily on the “last resort” and “proportionality” pillars.

Pope John Paul II opposed the 2003 Iraq War publicly and repeatedly. He declared: “War is always a defeat for humanity.”

Pope Francis has gone even further, questioning whether any modern war, given its toll on civilians and long-term destabilization, can still be called just.

The bar hasn’t been lowered. It’s been raised in response to drone warfare, proxy militias, and perpetual occupations.

So, What About War with Iran?

Apply Aquinas to today’s situation with Iran, and the results are devastating for the war-hungry:

- Proper Authority? Maybe — if Congress debates and declares war like it’s supposed to. However, for over 20 years, we’ve allowed presidents to act like emperors under the shadow of the 2001 AUMF. That’s lazy governance, not moral legitimacy.

- Just Cause? Iran funds proxies, sure. But the U.S. has assassinated Iranian generals on Iraqi soil, backed coups (1953, anyone?), and unleashed decades of sanctions. Whose injustice are we talking about here?

- Right Intention? If your goal is regime change, oil control, or unconditional support for a foreign ally, that’s not peace. That’s power politics. Aquinas would call it out.

- Last Resort? We haven’t even tried an honest diplomatic reset since the JCPOA was trashed. War is the easy button for leaders who refuse to do hard things.

- Probability of Success? It’s not nearly as high as the American media is trying to convince the American people.

- Proportionality? Iran is a major, well-armed country with asymmetric capability across the region. Escalating means regional chaos — and potential global fallout. This isn’t proportional. It’s a firestarter.

- Discrimination? Civilians must be protected; no targeting of noncombatants.

Ok, maybe we’ve got proper authority.

When “Liberation” Is a Lie

Let’s remember the last time we were told we’d be “welcomed as liberators.”

- Iraq was supposed to be a short, clean operation.

- Libya was just going to be a quick intervention.

- Afghanistan was meant to be a humanitarian nation-building project.

All three failed to meet the criteria for a just war. All three still destabilize their regions today. All three made American citizens less safe in the long run. And all were marketed as “just.”

Moral Laziness

We’ve stopped asking the tough questions because we’ve stopped believing there are real limits. War is sold like detergent: quick, clean, and necessary. And that’s where the doctrine of just war still matters.

It’s not about pacifism. It’s about restraint. About dignity. About humility, a value America has long abandoned. It demands that leaders pause, weigh costs, and count lives, not just U.S. soldiers, but the civilians who will be caught in the middle.

Just war isn’t a license to kill. It’s a test of whether you should fight at all.

Wrap Up

If the U.S. decides to go to war with Iran, it won’t be because the decision passed the moral test. It’ll be because those in charge ignored the test altogether.

We are no longer a nation led by moral statesmen. We are governed by bureaucrats who’ve turned the moral theology of war into an Excel spreadsheet and politicians who only care about what their donors want.

And yet… morality doesn’t go away just because you’ve stopped believing in it.

The question isn’t “Can we beat Iran?”

Should we fight at all?

Based on just war doctrine, the answer — for now — is a resounding no.

And that should awaken us all.

Want to send this to your Congressman, parish priest, or that one cousin who still thinks Netanyahu speaks for Christendom? Be my guest.

And don’t forget: this moral framework was built to protect you, too.

Comments: