The Cause of the Next “Black Monday”

Be afraid. Be very afraid.

So reads billionaire Paul Tudor Jones’ message to Janet Yellen.

Jones says that eight years of essentially zero interest rates have pushed stock valuations to their highest level since 2000 — right before the dot-com bust.

Nothing new there, you say?

But Jones also identified the ticking time bomb that could generate another October 1987-like explosion.

You’ve probably never heard of it — even though your portfolio might be loaded to the gunwales with financial dynamite.

But what could it be?

Answer anon. But first a check on the ammunition factory…

Dow down 31 today… S&P down seven… Nasdaq down six. Oil’s down about 50 cents.

The one patch of green?

Gold. Up about two bucks.

All in all: meh.

But that ticking time bomb…

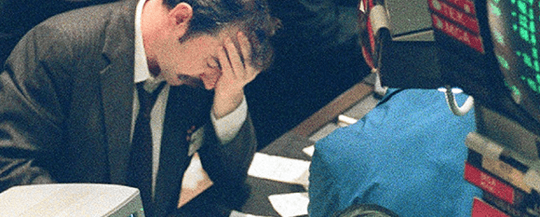

“Black Monday” — Oct. 19, 1987 — saw the largest one-day market crash in history. The Dow plunged 508 points that day. A 22% dive.

A similar event today would spell a 4,523-point one-day collapse.

What turned a bad day on Wall Street into Black Monday?

With all possible irony, something called portfolio insurance.

That’s a computer-based strategy that sells stock futures if markets begin to fall.

It lets investors minimize their losses when the market turns south.

In theory.

Portfolio insurance didn’t cause the initial sell-off in October ’87.

But once the initial selling started the computers went apes**t and the initial selling snowballed and snowballed and snowballed until the Dow lost 22% of its value in a single day.

As The New York Times styles it, Black Monday was caused by “computers programmed by fallible people and trusted by people who did not understand the computer programs’ limitations.”

The Times concludes with this gem:

As computers came in, human judgment went out.

A cautionary tale, as computers make more investment “decisions” than ever.

Paul Tudor Jones made a fortune in October 1987 — he tripled his money — by calling the crash in advance.

Even though they instituted reforms to prevent another Black Monday-type event (Plunge Protection Team?), Jones says today’s version of portfolio insurance can lead to another event just like it…

What is it?

Something called “risk parity.”

“Risk parity,” warns Jones, “will be the hammer on the downside.”

Risk parity attempts to distribute risk across several asset classes by allocating more money to lower-volatility investments and less to higher-volatility securities.

Instead of the usual 60% stock, 40% bond portfolio, risk parity funds theoretically reduce risk by limiting the more volatile stock weighting and increasing the less volatile bond weighting.

Portfolio insurance, in other words.

But according to Jones, risk parity funds have been buying a ton of stocks lately.

Why?

Because of extremely low levels of volatility in the stock market.

It’s all seashells and balloons on the way up. But when the fall comes…

And cometh the fall, the computers behind these risk parity funds will drop those stocks like nobody’s business.

And that could start the snowball rolling.

Or to return to our original metaphor… spark the fuse on the bomb.

Just like 1987.

Bloomberg paraphrasing Jones:

Because risk parity funds have been scooping up equities of late as volatility hit historic lows, some market participants, Jones included, believe they’ll be forced to dump them quickly in a stock tumble, exacerbating any decline.

Like Jones, Seabreeze Partners Management President Doug Kass thinks today’s low level of volatility masks the danger.

Kass thinks risk parity could soon write the October 1987 sequel — “Portfolio Insurance Act II”:

We all must recognize that when the market moves in a northerly direction the potential structural issues and emerging-market inefficiencies are camouflaged by the rising tide of higher stocks. But when, inevitably, the tide retreats and stocks fall, we may re-run the movie of October 1987 in Portfolio Insurance Act II.

Risk parity funds total about a half-trillion dollars.

That is, they’re large enough to work sorry damage before the fires are out on the next crash.

Remember, if Act II is a faithful sequel to Act I… it could mean a 4,523 blood-and-thunder drop on the Dow.

Even if a weaker script leads to, say, a 2,000- or even a 1,000-point intraday plunge, that’s no “dip.”

“You know neither the day nor the hour,” instructs Matthew 25:13.

And neither Jones nor Kass pretends to know the day or the hour of “Portfolio Insurance Act II.”

Nor do they know the severity of the script.

But we simply can’t escape the irony of it all.

It’s too rich for words, really… and let this one soak overnight…

“Portfolio insurance,” as it was in October ’87, could be the very fire it was designed to insure against…

Regards,

Brian Maher

Managing editor, The Daily Reckoning

Comments: