The War that Made the Fed; the Fed that Made the War

It’s Veterans’ Day, originally called “Armistice Day” to commemorate the end of the Great War (aka World War I) on Nov. 11, 1918. In this regard, it’s appropriate to discuss the war. And since this is an investment-oriented letter, we’ll address how the U.S. Federal Reserve helped finance it.

Below, we’ll look at how the 1914-18 conflict reshaped America’s system of national finance, and laid foundations that eventually brought us to the current situation of $38 trillion in national debt and $4,000 gold; plus, I’ll connect you with other points that might help on the investment side of life.

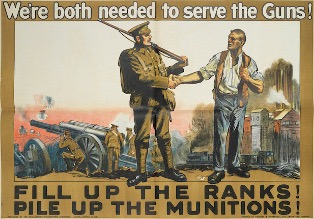

Great War recruiting poster. Courtesy Imperial War Museum.

Quick Housekeeping Items

First, and if you’re wondering… there’s no U.S. Mail delivery today. Most government offices – local, state and federal – are closed, even more so than usual when you consider the past 41 days. Most banks are closed, but stock markets are open; not bond markets, though.

If you’re on active military duty or a veteran, today you might (i.e., it depends on the franchise) get a free Egg McMuffin at McDonalds or avail yourself of other deals and discounts at fine establishments across the length and breadth of the Republic which you served.

Meanwhile, and from the look of things on Capitol Hill, America’s federal apparatus will soon reboot with enough funding to pay employees and recharge the pipeline of public benefits like SNAP, EBT and other alphabet soup programs. And if a trip to the airport is on your agenda you might enjoy a “normal” travel experience, but on this point do your own due diligence.

Now, let’s get back to the First World War, and discuss money and the Fed…

The Central Bank’s War

Most people don’t associate the Fed with World War I, but the institution played a crucial role in the event and I’ll go down that rabbit hole. Here are some historical basics.

Let’s begin on Friday night, December 23, 1913, meaning Christmas Eve weekend when few people (except deep insiders) were paying attention. President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act into law.

President Wilson signs Federal Reserve Act. Courtesy Federal Reserve History site.

To all intents and purposes this new entity was America’s central bank, although its creators didn’t label it as such due to strong public aversion to the idea. Recall, for example, how in 1832 President Andrew Jackson vetoed a bill that proposed to re-charter the Second Bank of the United States. Long story; not here.

Later, as 1914 unfolded the Fed stood up and began to work within the U.S. government system and of course played a role within the national economy. By design of its promoters, the Fed was intended to oversee a so-called “elastic currency,” not necessarily tethered to a fixed supply of gold in the vaults of America’s banks.

That is, the idea behind the Fed was to avoid monetary disasters like the Panic of 1907, when the federal government literally ran out of cash and had to borrow gold from banker J.P Morgan. The Fed’s mission was to issue credit – aka “create money” in the form of dollars – during tight times and ensure the general liquidity of the American economy.

Banker J.P. Morgan bailed out Uncle Sam after the 1907 Panic. Courtesy Library of Congress.

And who knows? The idea might have worked out well, except for what happened later in 1914, in August to be exact, when Europe went to war on all fronts. The short version is that Austria invaded Serbia; Russia mobilized; Germany mobilized; France mobilized; Britain mobilized; and pretty soon, almost every nation in Europe was fighting, to include combat across the globe from Africa to South America to the South Pacific.

Just a few months later, by about December 1914, pretty much every nation involved in the European fight was at or near technical insolvency. Governments had blown through their respective treasuries and could no longer pay the bills; but since when has that ever stopped a war, right?

Meanwhile, in those few short months, the European war sparked a business revival in the U.S. The short version is that innumerable banks and businesses sold and financed goods to belligerent nations, mostly to Britain, France and other “allied” parties because an Anglo-French naval blockade of Continental Europe kept Germany or Austria from importing too much from the U.S.

Insolvent or not, when Britain and France ran out of cash with which to pay for U.S. goods, they turned to credit markets. And in the U.S., President Wilson was okay with that. He supported American banks and businesses to make sales with credit, and this is also where the Fed comes in because it backed the banks’ issuance of credit.

Plus, under Wilson, the U.S. government went so far as to guarantee many billions of dollars’ worth of British and French bonds. This meant that if investors bought British or French paper, they would be assured of return on their investment if the bonds defaulted.

The takeaway here is that, among its first macroeconomic impacts, the Fed issued credit to enable Britain, France and other nations to buy U.S. materiel. This was inflationary at home in the U.S., and beyond doubt it enabled and prolonged the European war.

War, Bond Markets, and a Global Credit System

This Fed-backed wartime credit system continued to 1917, when the U.S. formally entered the war and began a vast, internal military buildup. Then, the requirements for U.S. government funding immediately skyrocketed, a macroeconomic issue that landed squarely at the front door of the Fed.

In other words, instead of just issuing and guaranteeing credit for Britain, France, etc., the Fed now had to fund a colossal American military effort that included bringing millions of men into the Army and Navy, plus building out a vast array of equipment, munitions and much more.

This U.S. military buildup led to new levels of federal borrowing at a historically unprecedented scale, via a series of what were called “Liberty” loans, and a later “Victory” loan issuance.

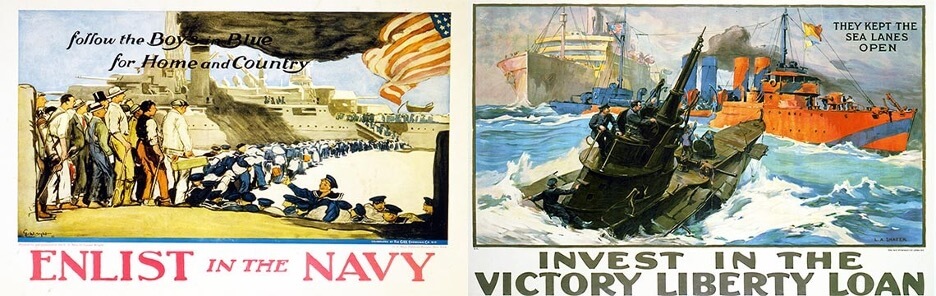

The Sine Qua Non of war: men and money. Courtesy U.S. Navy, History & Heritage Command.

In essence, the U.S. government sold Liberty Bonds during the war, and Victory bonds as the war concluded, all to raise money to fund military operations and then meet post-war obligations.

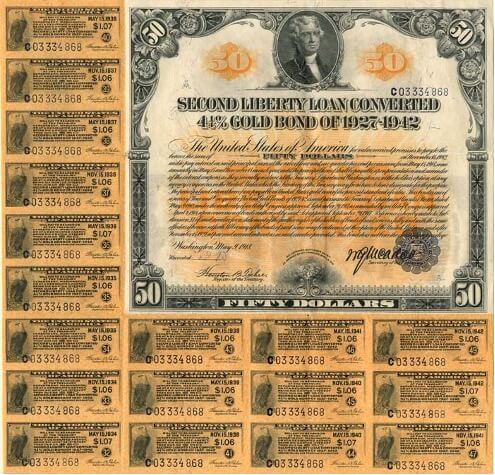

One interesting aside is that in those days before computers and electronic trading, bonds were printed on sturdy paper in fancy script, like this:

U.S. 1918, 25-year Second Liberty Loan, $50 face value @4.25%. Courtesy U.S. Treasury.

Obviously, there’s a $50 bond. And note the “coupons” printed on the same sheet of paper. But also, note the single serial number on the bond and all of the coupons. The idea was that after a period of holding, the bondholder would “clip the coupon” (i.e., literally cut it out with a pair of scissors), take it to a bank, and redeem it for the interest due.

All in all, millions of Americans and many foreigners bought these bonds, and thus was created a global-scale market for U.S. government debt. If there was any pre-war doubt about the idea of the U.S. dollar as a global-scale currency, the Liberty-Victory bonds sealed the deal.

Indeed, this 1910s-era, wartime government finance mechanism became DNA, so to speak, of modern American federal fundraising. World War I and the Fed created those above-noted bond markets that are closed on Veterans’ Day, today. And the pathway from financing the Great War to the current system of deficit spending and national debt is clear; it’s the same mechanism, updated to modern technology, to be sure.

Modern War Is Industrial War

Now, a few more comments on what all that Fed-credit bought, way back in the 1910s. Because the war was about far more than high finance, raising money and bond trading.

First, all of that financial credit to Britain, France and other nations allowed them to raise large armies and navies, send them into battle, and get entire generations of young people killed; and Germany and Austria lost similar, large numbers. Even today, that demographic echo bounces around across Europe if not the world.

Anymore, it’s difficult to envision the scale of manpower (and it was almost entirely men) who went into the armed forces of all belligerent nations; and this certainly includes the U.S. after President Wilson marched the U.S. formally into war in 1917. Obviously, the war distorted the entire scope of the population and labor force within Western nations. And people write long books about this; not here, not today.

Great War recruiting poster for British Army. Courtesy Dominicwinter.co.uk.

In a related macroeconomic impact, the global war required vast amounts of goods and services to equip all of these new armies and navies. And again, American and Fed-backed credit led to immense redirections of capital in economies across the world, and certainly within the U.S. And this was the true industrial origin of the modern military-industrial (and Congressional) complex that relies on large levels of government funding.

Great War poster depicting military and industry. Courtesy Bonhams.com.

For example, during the war U.S. President Wilson essentially nationalized America’s railway system, supposedly to expedite movement of troops, equipment and other supplies. The effect was several years of profound overuse and underinvestment, a situation from which the overall rail industry never really recovered.

Meanwhile, across America the war led to boom-times (excuse the pun) for agriculture and quite a bit of manufacturing, which led to large amounts of excess capacity that fell into disuse when the war ended in November 1918. And this led to a postwar recession, or more accurately a “mini-depression” that carried over to about 1921.

Also of interest, a youngish fellow named Franklin Roosevelt served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under President Wilson and learned quite a few things about how the U.S. government worked; especially, how to raise a lot of money and spend it in a hurry. More books on these matters, to be sure; but not here.

My goal with this note is simply to point out that it’s Veterans’ Day, remember the Great War, spur a few thoughts about all who fought and sacrificed, and highlight how the Fed played a major role in funding it all. Indeed, World War I was the war that made the Fed; and in another sense the Fed made the war. We still live with that legacy.

And a Bit More Housekeeping

If you’re interested, I can link you to some recent commentary on minerals, mining, the direction of the dollar and more. That is, I sat for two interviews in the past ten days or so.

First, I spent time with Joel Bowman, an old colleague from the Agora Financial days. Now, he runs a news and commentary service from Buenos Aires, Argentina, aka “the End of the World.” We discussed the recent, strong electoral performance of Libertarian President Javier Milei, along with investment-focused ideas in gold, silver, “military metals,” strength of the dollar… and even my recent dinner with Donald Trump, Jr. Here’s the connection.

Also, last week in New Orleans I sat for an interview with Charlotte McCleod of Canada’s Investing News Network. We discussed the sense of investor optimism at the Gold Conference. Then we dove into details of mineral and mining ideas. Topics ranged from gold and silver to platinum, rare earths, antimony and more. Here’s that link.

Finally, I’ll offer a strong plug to an old and dear friend, Jim Kunstler, who recently published another book, this one entitled, Look, I’m Gone; see here. It’s fiction, but with deep roots in reality, set mostly in New York City in the days just after the assassination of President Kennedy, 62 years ago on November 22, 1963. A young guy makes the rounds and discovers more about how the world works than he suspected he’d ever know, including a man-to-man talk with the Ambassador of the Soviet Union to the United Nations. But there’s more…

Jim lays out a rich picture of a very different New York, certainly compared with what we see in recent developments. Indeed, the Big Apple of Old offered a broad, deep landscape of mid-20th century America: subways that worked; well-run schools, museums and libraries; long-gone restaurants; formerly glorious hotels; a different era of Central Park; iconic theaters, and much else. Again, it’s fiction but Jim takes the reader through a time tunnel, and on an adventure to a lost world. See here.

And that’s all for now. Thank you for subscribing and reading.

Comments: