The Final Secret of the Federal Reserve

Mark your calendar for tomorrow, Wednesday, April 23, at 2pm Eastern Time for a live broadcast from Jekyll Island, Georgia, where the U.S. Federal Reserve was conceived. Tune in, at no cost to you.

Paradigm Press Group is hosting a special, online, subscribers-only event at ground zero of the U.S. dollar as we know it (yes, “as we know it” because it used to be something very different). We’ll come to you from the exact spot where America’s modern monetary history kicked off.

Join us as we discuss some of that monetary history and much else; definitely, we’ll present investment themes and ideas focused on the here and now.

View the schedule, and event here.

At tomorrow’s Jekyll Island event, we’ll address markets, sectors and trends. We’ll offer thoughts on the dramatic upward moves in the price of gold over the past year. How much higher, or perhaps lower? We’ll say what we think.

We’ll tie it all together in the context of the dollar’s future, global trade, tariffs, geopolitical moves – including war and potential war in Europe, the Middle East and Asia – and how to navigate your way through the current tumult.

You’ll hear our distinguished colleague Jim Rickards, plus Paradigm editors Sean Ring, Dan Amoss, Zach Scheidt, Aaron Gentzler, and yours truly as we gather in the historic room of a historic place where America’s modern central bank was hatched.

And oh, if only those walls could talk! Channeling the past, we might hear the echoes of a small group of insiders – indeed, the well-heeled insiders of all well-heeled insiders – who secretly met in November 1910 to lay the foundations of the Fed, and then as history unfolded to hijack America’s money, if not its destiny.

Jekyll Island Clubhouse, circa 1910. Courtesy U.S. Federal Reserve Bank.

Sad to say, most history courses don’t come close to approaching what happened there, at Jekyll Island. That’s if those courses mention it at all. Yet that 1910 meeting was among the most secretive and impactful gatherings in America’s long story, and it’s why we chose the venue.

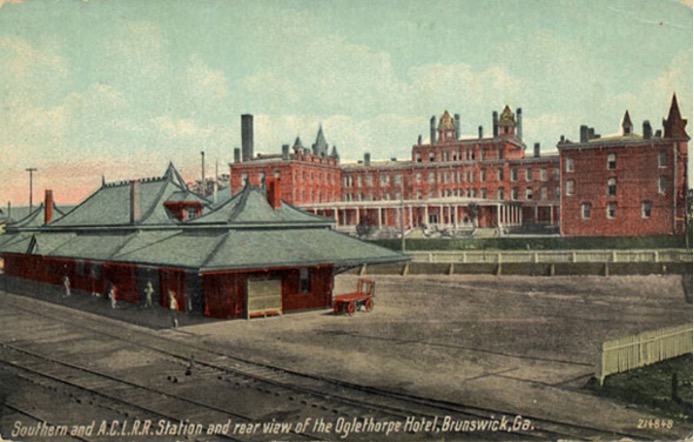

Back then the parties and their entourages arrived at different times, by separate trains, at a small station near Brunswick, in southeast Georgia, about halfway along the coastline between Jacksonville and Savannah.

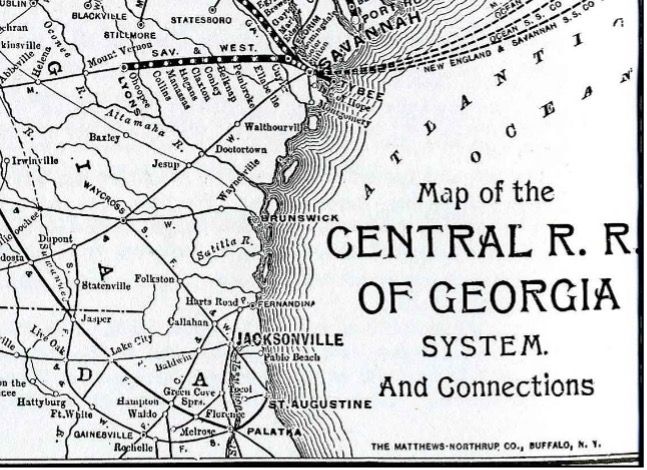

Old railway map showing Brunswick, Georgia. Courtesy Georgia Historical Society.

To maintain cover, the passengers rode in separate, non-descript railway cars. Then in the dead of night, via different ferryboats, they crossed over a bay from the mainland. All this while, in their respective homes near New York, everyone left a misleading story about their absence; namely, that they were on a duck hunting trip.

Brunswick, Georgia train station, circa 1910. Courtesy U.S. Federal Reserve.

Afterwards, none of the principals even acknowledged their get-together until over two decades later, in the 1930s during the depths of the Great Depression.

Yet over time, the shadowy work of these individuals fundamentally altered the arc of American history. Knowingly or perhaps not, they changed the country’s money, culture, politics, and the very structure of governance under the original Constitution of 1787 and Philadelphia fame.

Today, over a century later, we live with this Jekyll Island legacy. Some argue that it was all a good faith effort to reform the country’s economy; yet in other respects the gathering opened the monetary equivalent of Pandora’s Box.

And now, here we are just a day out from our Jekyll Island event, where our Paradigm Press Group team will reveal the final secret of the handiwork knitted by these moneyed American oligarchs.

Birth of the Creature from Jekyll Island

The long tale of America’s money and wealth creation, and how it shaped culture and politics has deep roots into colonial days. But for our purposes, and with tomorrow’s focus on Jekyll Island, let’s begin a few years earlier in 1906, and in particular with the San Francisco earthquake.

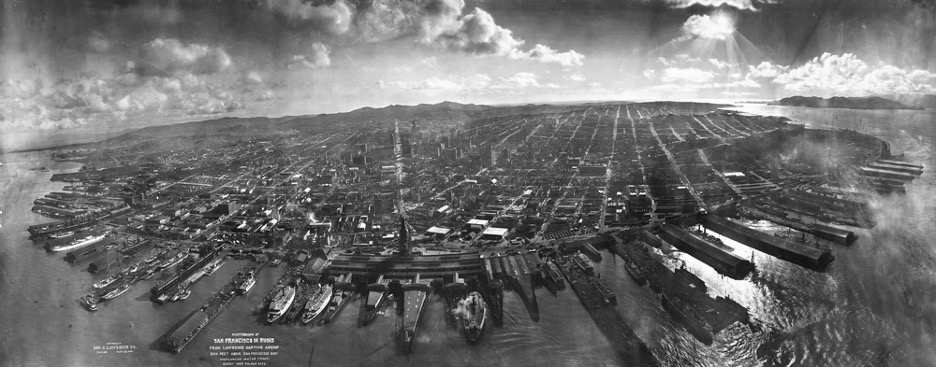

Aerial image of San Francisco after 1906 earthquake. Courtesy U.S. Geological Survey.

That is, on April 18, 1906, a massive earthquake occurred in the San Francisco region. Looking back with modern methods, the magnitude is estimated at 7.9; in other words, this event was highly destructive and truly a city-buster. All that seismic energy knocked down many buildings; and then, fires raged for several weeks and essentially destroyed the city by the bay.

As the fires burned, it was evident that the costs of dealing with such a disaster were immense. Keep in mind, too, that this was long before the U.S. government was a dominant force within the overall economy. Indeed, total annual federal expenditures in the early 1900s amounted to about 3% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), and about half of that was from the sale of Post Office stamps.

Definitely, back then, there was no FEMA, no military helicopters delivering aid, no highways and trucks hauling in supplies. The cleanup was all about local people digging out with picks and shovels, wheelbarrows, and horse-drawn wagons.

As one might expect, though, much of the real estate and other property in San Francisco was insured, and in due course people filed claims. Then between insurance company payouts, as well as banks that shifted funds West to pay for rebuilding the ruined California city, liquidity quickly and dramatically tightened within the U.S. economy.

All of this makes for a long story (not here), but the key point is that this rapid transfer of vast funds to pay for the San Francisco earthquake weakened the overall U.S. economy. The hit to the country’s money supply was so sharp and deep that America went into an economic “panic” in 1907.

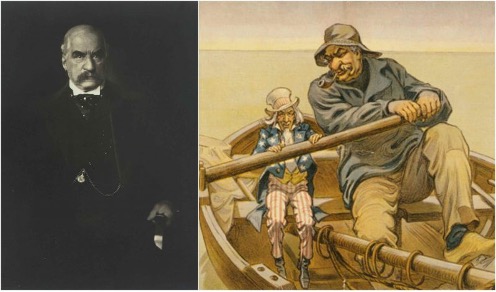

During this panic, stocks sold down, liquidity dried up, lenders called-in loans, many banks and businesses went bust, railways and farms failed, and people across the nation lost jobs. At one point, even the U.S. Treasury was short of funds, and in a politically embarrassing situation the government of the United States of America took out loans from banker J.P Morgan.

Banker J.P. Morgan, and political cartoon of the 1907 era depicting him dominating U.S. government. Courtesy VintageNews.com.

Keep in mind that the early 1900s were an era of hard money. That is, as a matter of law the U.S. was on a gold standard which meant, in the immortal words of banker Morgan, that “gold is money, everything else is credit.” And that was the problem: the amount of credit within the economy, or lack of it.

J.P. Morgan and many others in his orbit believed the architecture of the U.S. financial system was inherently flawed, and there was history to back them up. Since the 1790s, a general lack of liquidity and coordination of money across the economy routinely led to financial panics that occurred, on average, every fifteen years. These events forced financial institutions to suspend operations, if not fail, and always triggered recessions.

It was not, however, that the U.S. lacked inherent wealth. Across the landscape of the country was one treasure trove after another, from forests and farmlands to minerals and ample water. And on the national aggregate of books and ledgers, American banks held significant reserves of cash in their vaults, which meant gold. But these funds were dispersed and scattered across the country, hidden away in thousands of distinct vaults. There was no means to coordinate all of this wealth towards any national purpose.

Under this setup, bank reserves tended to freeze up during crises, which prevented them from being put to immediate good use. While during normal times, large amounts of funds tended to gravitate toward money centers like Chicago, New York and Boston, where bankers made a lucrative business of issuing loans to stock speculators.

Broadly, in the early 1900s American banking insiders believed that the country’s monetary and bank system was a recipe for a seesaw mix of capital immobility and volatility, always leading to instability. They wanted to make changes.

The answer, the bankers believed, was a “central” bank, meaning a national-scale bank that monitor and coordinate the nation’s regional and local banks. This different kind of institution would improve oversight and control over all that aggregate wealth deposited in disparate vaults scattered across the plains, towns and cities of the Republic.

In short, this was the central bank idea hatched at Jekyll Island. And it was the first step toward creating the Federal Reserve three years later, in December 1913.

1907 St. Gaudens $20 gold coin. Screen grab from eBay.

The mission of this new Fed idea would be to transform the dollar from a firm and fixed amount of gold ($20 per ounce in those days), into a so-called “elastic” currency. In other words, in times of economic stress, the central bank could expand the nation’s overall money supply.

Meanwhile, with a central bank to back up the national money supply, the U.S. Treasury would never again lack for dollars, and never again be forced to terms from a wealthy banker like J.P Morgan.

At the same time, this central bank idea was a recipe for how to create and spend dollars, regardless of how much gold was or was not in government vaults, let alone in private banks.

In times of crisis, the Fed would create currency and adjust money supply to support the needs and demands of the macro-economy. Later, when economic times improved, the Fed and America’s federal government would somehow remove those dollars from circulation; the Fed-bucks would vanish into the ether. Well, that was the idea, anyhow.

And then history happened, the past 110 years of it. No need to recount any details at all, other than here we are in 2025 with the U.S. government $37 trillion in debt, and interest of nearly $2 trillion of interest. And there’s not nearly enough productive capacity in the economy to pay it down, let alone pay it off.

Which brings us to tomorrow, Wednesday, April 23 at 2pm eastern time, live from Jekyll Island.

From there, we’ll discuss all of this, the history and more. Where is the economy going? Gold? Markets? Investment ideas? I hope you can make it, and with that I’ll sign off.

Add this (free) event to your calendar, and attend, here.

Thank you for subscribing and reading.

Comments: