One Misfortune Away From Insolvency

We can summarize the changes in our economy over the past two generations with one word: precarity, as life for the bottom 90% of American households has become far more precarious over the past 40 years, despite the rising GDP and “wealth” as measured in phantom capital.

This reality is expressed in the portmanteau word precariat, combining proletariat (someone whose livelihood comes from their labor) and precarious: Outside of government employment, work has become far more precarious.

Where it was still common 40 years ago to work for a company for much or most of one’s career and have a private-sector pension, now private-sector pensions have vanished, replaced by self-managed 401(k) funds, and private-sector work is characterized by a series of not just job changes but career changes.

The source of one’s livelihood can dry up and blow away almost overnight, and to fill the hole many turn to gig work with zero benefits that saddles the worker with self-employment taxes (15.3% of all earnings, as the “self-employed” gig worker must pay both the employee and the employer shares of Social Security-Medicare payroll taxes).

This isn’t true self-employment, of course, as true self-employment means the owner-worker can hope to extract the full value of their labor; in contrast, much of the value of the gig work is skimmed off by corporate platforms (Uber et al.). The gig worker is a precariat wage-slave, not a self-employed owner of their own labor and enterprise.

Is This Progress?

Forty years ago, households with health care insurance being driven into bankruptcy by medical bills was unknown. Now this is commonplace. We’re forced to ask, what exactly does “insurance” even mean if our share of the medical bills is so burdensome that we’re forced into insolvency?

This is just one of many examples of the increasing precarity of life in America. Need dental work? “Insurance” covers only the basics; the rest requires savings, an inheritance, a line of credit or a top-10% income.

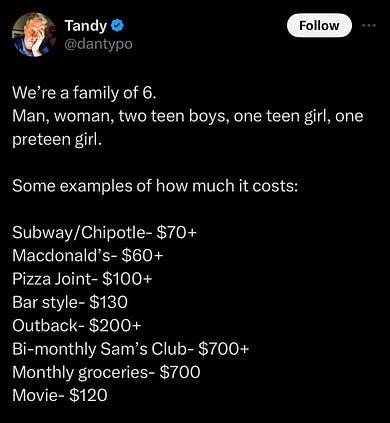

Speaking of income, even a substantial earned income doesn’t go that far nowadays. Consider what a typical family spends on what we consider middle-class birthrights: eating out, going to a movie, etc.

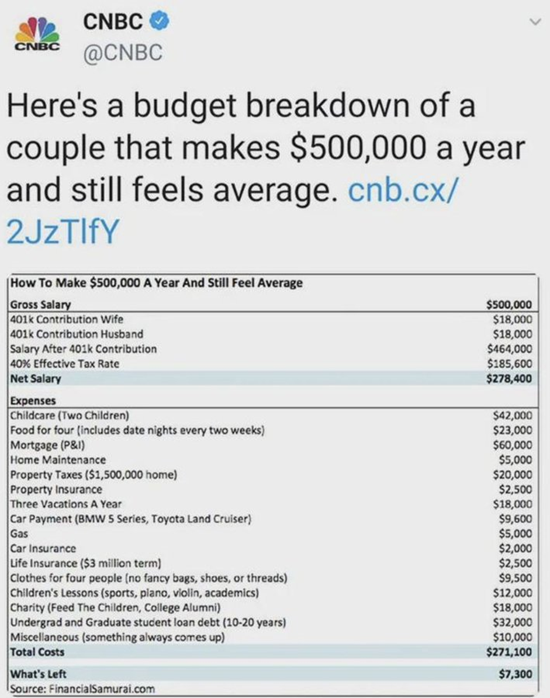

This budget of a household earning a top-1% income (top 2% in high-income states) of $500,000 is interesting on several fronts.

Those living in lower-cost states may view it as bloated beyond belief, while those living in New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco et al. will view it as entirely realistic: Yes, property taxes are $20,000, “enrichment” childcare costs $42,000 and so on.

Who Can Afford It?

What’s not realistic is $5,000 for home maintenance and $18,000 for three vacations a year. Given the age of American houses (40 years being average), the poor quality of a significant portion of recent construction and the soaring cost of labor, $5,000 doesn’t buy much in the way of maintenance.

A more realistic estimate for pretty much anything serious is $20,000, and $50,000 is remarkably commonplace for even modest kitchen makeovers. The $18,000 in charitable donations may be sucked up by a new roof.

As for vacations, unless it’s a very short trip, a camping trip or travel to a low-cost destination, $6,000 per vacation may not be realistic.

The point of this exercise is to examine the buffers needed to survive a serious misfortune, such as losing one’s job or a medical crisis.

Two generations ago, costs were lower and households generally had enough savings or credit to cover the emergency expense or survive a bout of unemployment. With costs now prohibitive, modest savings are no longer enough.

As a result, a significant percentage of households that are considered middle-class are one misfortune away from insolvency.

A Tale of Two Classes

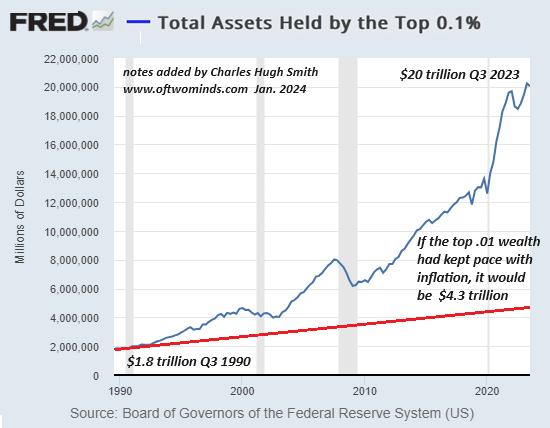

The concentration of income and wealth into the top 10% isn’t just a statistical abstraction; in the real world, it means the buffers of the bottom 90% have thinned while the buffers of the top 10% have increased: For the family holding hundreds of thousands of dollars in 401(k) accounts and sitting on $1 million in home equity, a $25,000 medical or home repair bill is an inconvenience, not a push off the cliff into insolvency.

This precariousness extends into small business as well. Costs have soared and buffers have thinned. A great many small enterprises are one misfortune away from closing/insolvency.

While I focus attention on the way globalization and financialization have hollowed out our economy and increased the precarity of labor, in the larger context we can identify these structural drivers of decay:

The Drivers of Decay

1. The balance between labor and capital has been skewed to capital for 50 years. Labor’s political power and share of the economy have declined while capital’s political and economic power has become dominant. This has driven income-wealth inequality to extremes that are destabilizing the economy and the political-social orders.

Increasing the sums labor can borrow to keep afloat only works until debt service consumes all disposable income, crushing consumption. The end result is mass default of debt and the erasure of debt-based “assets” held by the financial elites (top 10%).

Labor will have to restore the balance with capital or the system will collapse in disorder. History is rather definitive about this causal chain.

2. Process and narrative control have replaced outcomes as the operative mechanisms and goals of the status quo.

The illusions of limitless “progress” and “prosperity” have generated a mindset in which outcomes no longer matter, as “progress” and “prosperity” are forces of Nature that can’t be stopped, so we can luxuriate in Process — completing forms and compliance documents, submitting reports to other offices, holding endless meetings to discuss our glacial “progress,” mandating more Process, elevating managers who excel at Process — with the net result that building permits that were once issued in a few days now take months, bridges take decades to build and incompetence reigns supreme.

To obscure the dismal outcomes — failure, delays, poor quality, errors — narrative control is deployed, expanded and rewarded. The managerial class has been rewarded and advanced not for generating timely, on-budget, high-quality outcomes, but for managing Process and Narrative Control: Everything’s going great, and if it isn’t, the fault lies elsewhere.

The net result of this structure is that the competent either quit in disgust or or are assigned to Siberia, while the incompetent are elevated to the highest levels of corporate and public-sector management.

Monopolies

3. The dominance of monopolies and cartels has fatally distorted markets and politics, undermining the foundations of everyday life.

By eliminating competition and buying political-regulatory complicity, monopolies and cartels lock in ample, stable profits, profits that are increased by squeezing labor and reducing the quality and quantity of goods and services, to the point that quality services and goods are either luxuries available only to the elite or simply unavailable at any price, as the knowledge, systems and values required to produce high-quality goods and services have been irrevocably lost.

4. The dominance of digital communications in everyday life has increased the unpaid shadow work we’re forced to do and injected new forms of narrative control, digital hypnosis, addiction and derangement into daily life that cannot be reversed in any meaningful way other than drastically limiting our exposure to the toxic flood tide.

So where does this leave us? We’re on our own.

The status quo is incapable of unwinding the fatal distortions generated by the dominant economic structures, and so it is also incapable of “saving” us from being seated at the banquet of consequences. This is why the only rational response is to focus on increasing our self-reliance.

Rather than becoming enraptured by the apologists and cheerleaders proclaiming everything’s great, launching a lifeboat and setting a course for land is a strategy with much higher odds of success.

Like what you’ve read? Go here for more.

Comments: