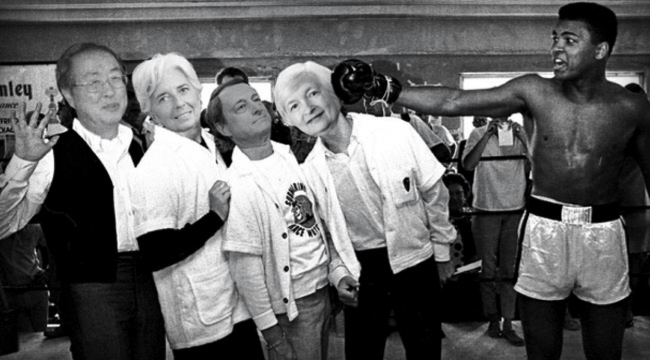

The Global Monetary Elites Are Being "Rope-a-doped"

Muhammad Ali is undoubtedly one of the greatest boxers of all time. He calls himself “the Greatest,” but among fans and sportswriters, he is also called “the People’s Champion,” because of his popularity and ability to connect with everyday citizens around the world.

His lifetime record in professional fights was 56-5 with 37 knockouts. Before becoming a pro, he won a gold medal for the U.S. Olympic boxing team in the 1960 Olympics in Rome.

Ali did not look like the most intimidating boxer in the ring; others like Sonny Liston and Joe Frazier had fiercer demeanors. But Ali had a combination of smarts, agility and creativity that none of his opponents could match. He declared he could “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee” in the ring. This was a way to capture the combination of his fluid motion and lightning-like knockout punch.

Ali also invented a technique he called “rope-a-dope.” The idea was simple, but few boxers could pull it off. Ali would lean back on the ropes and absorb punishment from his opponent, even pretending to be weakened. Then he would bounce off the ropes, strike back and inflict a powerful combination of painful blows on his opponent.

The point of rope-a-dope was not that it worked once, but that it worked repeatedly. Opponents could not resist the sight of a seemingly weakened Ali leaning on the ropes. The result was always the same — a refreshed Ali would lash out, cause real damage and eventually win the fight.

The global economy today can also be understood as an exercise in rope-a-dope by forces of deflation versus the forecasts and policy experiments of central bankers.

Deflation is caused by a combination punch of demographics, debt, deleveraging and technology. It weakens real growth, and it reduces nominal growth even more. In recent years, both the U.S. and Japan have periodically shown negative real growth, but nominal growth has been even lower because of the impact of deflation.

Real growth makes us richer, but nominal growth is how we pay debt, since debts are nominal — you owe what you owe regardless of the real value. Low real growth is a disaster for social well-being, and low nominal growth puts us on the same path as Greece. The one-two combination is toxic.

Meanwhile, the global monetary elites — central bankers, the IMF, finance ministers and professors — keep predicting higher growth, and they keep printing money to get it. They continually expect better growth in the next quarter, the next half or the next year.

They act like the opponents of Ali and believe that deflation and weak growth are “on the ropes.” One more dose of QE or one more interest rate cut will be all it takes to knock out deflation and win the fight.

Yet every time the monetary elites are ready to declare victory, deflation bounces off the ropes, charges to the center of the ring and hits their policies with vicious GDP punches. What is amazing about this pattern is not that it happened at all but that it keeps happening.

Monetary elites are like Muhammad Ali’s opponents in the ring. They fall for the same trick every time. Ali showed that in order for rope-a-dope to work, you need a “dope” — someone who just doesn’t understand what’s happening. The monetary elites seem to qualify as those who just don’t get it.

To illustrate this phenomenon, look at this chart of quarterly GDP growth, shown as an annualized percentage change:

Growth in the third quarter of 2012 was 2.5%, slightly above the post-2008 average. But it collapsed in the fourth quarter and was almost negative. Growth in the third and fourth quarters of 2013 was robust, averaging about 4% over both quarters. Then it collapsed again in the first quarter of 2014 to negative 2.1%.

Growth in the second and third quarters of 2014 was the best in this recovery, averaging almost 5%. But then it fell back to trend in the fourth quarter and collapsed in first quarter of 2015, when it was again negative.

The pattern is obvious. We can call it deflationary rope-a-dope. Collapses in Q4 2012, Q1 2014 and Q1 2015 show how deflation bounces off the ropes and bloodies the best-laid plans of the central banks. Every time growth picks up due to money printing, interest rates cuts and currency wars, deflation just bides its time.

Deflationary and disinflationary tendencies persist because the problem with the global economy is not cyclical, it’s structural. This means that monetary remedies can at best produce temporary results but will not permanently fix the problem. A good comparison is the persistence of the Great Depression from 1929-1940.

After a brutal decline from 1929-1933, the economy did pick up from 1933-1936, but then collapsed again in 1937. The monetary remedy of devaluing currencies against gold — used by the U.K. in 1931 and the U.S. in 1933 — produced temporary gains but did not permanently fix the problem.

Capital was on strike and refused to invest until uncertainty about government policy was resolved. Consumers were also uncertain and saved rather than spend what money they had. It was only when the economy was restructured to a war footing in 1940 that growth resumed. Apart from war, a robust peacetime economy did not reemerge until the Republican tax cuts of 1946.

There is some evidence that global monetary elites are waking up to the rope-a-dope effect of deflation. The IMF and Federal Reserve have lowered their respective global and U.S. growth forecasts in recent weeks. But there is still no evidence that the monetary elites understand the cure for global economic malaise.

What is needed is not more money but smart infrastructure investment, lower taxes and smart regulation (which means more regulation for banks and less for businesses and entrepreneurs), among other structural remedies. Unfortunately, none of these policies is on the political horizon.

The “indications and warnings” on which my newsletter advisories rely have been signaling a global growth slowdown even more pronounced than the monetary elites are willing to admit.

The deceleration of growth in China is impossible to ignore. The six-month super-spike in the Shanghai stock index was an effort to solve a credit collapse by issuing equity to millions of unsuspecting first-time investors. Now the stock bubble has collapsed also.

With equity and credit markets in distress and no ability to devalue the currency because of the new yuan-dollar peg, growth in China is on a downward spiral. The same is true in Brazil, due to mismanagement and corruption, and in Russia due to sanctions.

Commodity producers such as Australia will suffer along with China. Greece is resolved for the moment, but a stronger euro will slow growth in Europe. The U.S. is not immune from this global slowdown — the world is too interconnected.

Certain stocks have come down lately in line with this global growth decline. But some have not. The key for investors is to find a stock or sector that is still flying high and seems unaware of the rope-a-dope surprise coming in the second half of 2015.

Regards,

Jim Rickards

for The Daily Reckoning

P.S. Be sure to sign up for The Daily Reckoning — a free and entertaining look at the world of finance and politics. The articles you find here on our website are only a snippet of what you receive in The Daily Reckoning email edition. Click here now to sign up for FREE to see what you’re missing.

Comments: