Same Currency War, New Battle Phase

The current global currency war started in 2010. My book, Currency Wars, came out a little bit after that. One of the points that I made in the book is that the world is not always in a currency war. But when we are, they can last for a very long time. They can last for five, 10 or 15 years, sometimes longer.

And so it’s really not a surprise that here we are in 2014 talking about currency wars because it’s the same on that’s been going on. A lot of what you read or see on the TV is after some policy move by, let’s say, Japan to weaken the yen. And reporters will say: “Hey, there’s a currency war going on,” or “There’s a new currency war.”

I roll my eyes a little bit and go: “No, this is the same one, the same currency war; it’s just a new phase or new battle.”

So yes, it is going on. And it does have a lot of explanatory power. It’s one of the most important things going on in economics today. I think a year from now, I’ll be writing to you and we’ll still be talking about it.

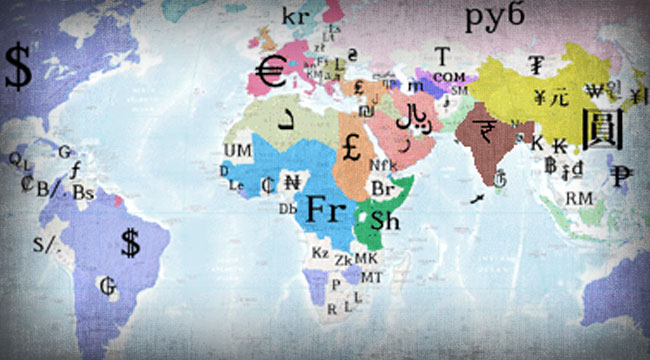

What is a currency war, in a nutshell? They typically happen when there’s not enough growth in the world to go around for all the debt obligations. In other words, when growth is too low relative to debt burdens.

When there’s enough growth to go around does the United States really care if some country somewhere around the world tries to cheapen its exchange rate a little bit to encourage a little foreign investment? Not really. It’s almost too small to bother with, in the scheme of things. But when there’s not enough growth to go around, all of a sudden it’s like a bunch of starving people fighting over the crumbs.

“This is the same currency war; it’s just a new phase or new battle”

Now everybody cares about currency cross rates because it’s a way to either import inflation in the form of higher import prices. Remember, when you lower your exchange rate, people in your country have to pay more for imported goods — and the United States is a net importer. We buy more from overseas than we sell.

The immediate impact of a cheaper dollar is to increase our costs — importing inflation — which is exactly what the Fed wants. How many times have you heard the Fed say they want 2% inflation? They analyze it over and over and over. We don’t have 2% inflation right now. It’s not even close. But they need to get there.

One of the ways they do it is to cheapen the dollar. The effect, of course, is it promotes exports. In the case of the United States, something like Boeing Aircraft, which are big ticket items, are competing with AirBus in France or Embraer in Brazil or Bombardier in Canada.

There are a few aircraft manufacturers around the world. Not that many, but we compete with them. And so a cheaper dollar, in theory, helps Boeing sell a few more planes. But from the US point of view, that could be jobs and growth in the US. So there are perceived to be benefits.

Now, a lot of those benefits are illusory. But it’s very, very appealing to politicians because he or she can stand up and give the speech that I just recited. Namely, “Hey, it’s good to have a cheap dollar because we promote jobs.” But the reality is, it doesn’t promote jobs. It just promotes inflation.

You’re actually better off with a strong currency because that attracts capital from overseas. People want to invest in the strong currency area, and it’s that investment and those capital inflows that actually creates the jobs. So as usual, the politicians and the central bankers have it completely wrong. But they’re not listening to me or necessarily reading my newsletter, Strategic Intelligence.

They think this is a cheap fix. All around the world you’re seeing countries cheapen their currencies. They do this basically by cutting interest rates or intervening in markets. They do it ostensibly to help growth. But it doesn’t really help growth, it just causes inflation.

Think of a bunch of starving people fighting over a few crumbs. That’s what happens when there’s too much debt in the world and not enough growth. That’s what a currency war is. It’s going on now. It will continue to go on. It has enormous explanatory power.

You’re trying to figure out growth… or interest rate policy… or you’re trying to figure out what sectors to invest in… are we going to get inflation or deflation; all those big questions that you wrestle with. You can get some clarity and visibility on all of them just by understanding this dynamic of the currency wars.

This is the Mick Jagger theory of economics. Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones had a song called “You Can’t Always Get What you Want.” And the point is, the Fed wants inflation, but that doesn’t mean they automatically get it because there are other forces at work.

You can understand Fed policy as an effort to cheapen the currency and get inflation. But the dollar is very strong. It’s the strongest it’s been in about eight years. A lot of people think this is the all-time high for the dollar. It’s not.

The all-time high for the dollar was in the early ’80s, in the early part of the Reagan administration. You go back and look at the dollar index in mid-1980s — ’84, ’85, right in there — that was the all-time high for the dollar. From ’83 to ’86 was a pretty good economic period.

GDP, in real terms, grew 16% in three years. That’s over 5% a year — much stronger growth than we’re experiencing today. So that’s a good example of the point I made above, that a strong dollar can actually lead to strong growth because you’re growing with investment and productivity gain.

The Fed wants inflation, but that doesn’t mean they automatically get it

It’s not just cheap goods and inflation. Having said that, yes, the dollar is the strongest it’s been in about seven years, right now. And the reason for that is very simple. Markets expect US rates to go up in 2015. They expect our trading partners to continue to print money; namely the Japanese and the Europeans.

So, the Japanese are printing money. They’re going to run out of ink, they’re printing so much money. The Europeans, not so much but the expectation is there. Everyone’s expecting Mario Draghi to engage in some kind of quantitative easing.

I don’t think he’s actually going to do very much — mainly because of the German influence. That’s my view and my analysis of how the ECB works. But so what? The market expects him to. And the market expects US interest rates to go up in 2015.

I don’t think that’s going to happen, either. My view of how things are going to play out is the opposite of what the market expects.

But let’s talk about the market because that’s where you trade and invest, and it has the last word. Right now, markets are expecting US rates to go up next year, and for Europe and Japan to keep rates low — even negative — and to print money.

If you’re an investor, you’re probably thinking: ‘Well, I’d rather invest in the place that is going to give me a return. If I invest in Japan or Europe, I might get a negative return because the currency is going down, the rates are low — maybe even negative. If I invest in the US, I’ll get a positive return because the Fed’s going to raise rates and give me something on my money. Therefore, investors are flocking to the United States and that’s why the dollar is strong.

People always look at cross rates, like the US-euro rate or the US-yen rate or whatever, in terms of trade surplus and deficit, and things like purchasing power.

Those are interesting concepts but those are not what determine exchange rates. Cross rates are determined by capital flows, pure and simple. Now, capital flows have their own dynamic, but right now capital is flowing into the United States, away from these other areas, partly because the expectation of stronger growth and stronger rates. That’s why the dollar is stronger.

That explains what’s going on. Now, the question is, ‘Okay, got it, but how much of that is gonna play out?’ In other words, will US rates actually go up in 2015? Will Draghi actually do the quantitative easing people expect? If the answer to those questions is no, then for other reasons you’re not going to see rate increases and you’re not going to see Draghi do very much, then this dollar strength and euro weakness could turn on a dime.

Regards,

Jim Rickards

for The Daily Reckoning

P.S. I recently launched a brand new investment letter called Strategic Intelligence. Besides my occasional essays on The Daily Reckoning, it will be the only place to receive my ongoing analysis. Click here to subscribe now. When you do you’ll receive a free copy of my book… three free reports I’ve written… access to my live monthly briefings and more — all for just $49 per year. Click here for more details.

Comments: