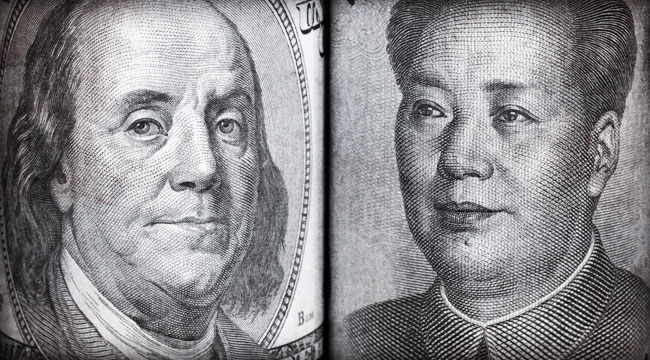

A Game of Currency Wars

Imagine for a moment: China’s leaders decide they want to dump 10% of their U.S. Treasury holdings — about $100 billion worth — in exchange for gold held at West Point. Even with a gold price of $1,000 an ounce, that’s 2,840 metric tons of gold — more than one-third of the U.S. government’s official gold holdings.

James Rickards paints a powerful word-picture in his book Currency Wars: “Chinese naval vessels arriving in New York Harbor and a heavily armed U.S. Army convoy moving south down the Palisades Interstate Parkway from West Point to meet the vessels and load the gold on board for shipment to newly constructed vaults in Shanghai.”

Now consider this: In 2008, China did indeed redeem $100 billion of Treasuries. And up until 1971, the U.S. would have had to surrender the gold.

“While this example may seem extreme,” Rickards writes, “it is exactly how most of the world monetary system worked until 40 years ago… America has, in fact, run trade deficits large enough to wipe out its gold hoard under the old rules of the game.”

Jim Rickards is no ordinary hedge fund manager. Lots of guys boast a 35-year career on Wall Street. Only Rickards is also a lawyer who was the chief negotiator during the 1998 rescue of Long-Term Capital Management — in which 14 of the world’s biggest banks ponied up $3.6 billion to prevent a global financial meltdown. And only Rickards is a consultant to the Pentagon who walked senior military planners through their first-ever “financial war game.”

Currency Wars opens with a two-chapter account of this war game — held at the Warfare Analysis Laboratory in Laurel, Md. — a strategy room whose website boasts “14 plasma displays for defense exercises” and “3-D scenario modeling and visualization.”

The financial war game was made more intense by the fact it took place amid the market panic in late 2008 and early ’09. We won’t give too much away here; suffice it to say Team Russia announced it would accept only gold in exchange for its oil and gas — no dollars. Then Team China made its own move to “tighten the noose around the U.S. dollar’s neck.”

As it happened, on the second and final day of the war game, Russia’s Vladimir Putin declared of the dollar, “The one reserve currency has become a danger to the world economy: that is now obvious to everybody.”

Rickards believes the real currency war presaged by Putin began in early 2010. He labels it Currency War III.

“Currency wars,” Rickards writes in his book, “are fought globally in all major financial centers at once, 24 hours per day, by bankers, traders, politicians and automated systems — and the fate of economies and their affected citizens hang in the balance.”

On Jan. 27, 2010, President Obama fired the first volley of Currency War III in his State of the Union speech. He announced the National Export Initiative. Its aim — to double U.S. exports in five years.

“The traditional and fastest way to increase exports had always been to cheapen the currency,” Rickards writes in Currency Wars. And everyone around the world knew it.

Later in 2010, the Federal Reserve stepped in with a second round of “QE,” or money printing. “By using quantitative easing to generate inflation abroad, the United States was increasing the cost structure of almost every major exporting nation and fast-growing emerging economy in the world all at once.

And so began another race to the bottom, a new round of competitive devaluations. “We’re in the midst of an international currency war,” declared Brazil’s finance minister Guido Mantega in September of 2010, “a general weakening of currency.”

No one will be left untouched by Currency War III, but Rickards says it will take place in three major theaters. In two of the theaters, the combatants have mutual aims. The third is the most likely source of outright conflict.

The Atlantic theater is the balance between the United States and the eurozone. “The euro and dollar,” writes Rickards, “are best understood as two passengers on the same ship… moving at the same speed, heading for the same destination.”

The euro topped at $1.59 in July 2008 and bottomed at $1.10 in June 2010. As we go to press, it’s at $1.29 — essentially where it was in early 2007, and again in early 2011.

That relative stability is no accident: Washington aims to prop up the euro to the point of the Fed engineering a secret bailout of European banks in 2008 — $3.08 trillion in loans that became public only in 2011.

The Eurasian theater of the war, meanwhile, is the balance between Europe and China. “China has a vital interest in a strong euro,” Rickards writes — not least because the European Union is China’s largest trading partner, larger even than the U.S.

Bottom line: “Europe, China and the United States are united in their efforts to avoid a euro collapse despite their mixed motives and adversarial postures in other arenas.”

Which brings me to the Pacific Theater — the big show.

The U.S. trade deficit with China was less than $50 billion in 1997. By 2006, it swelled to $234 billion. Politicians grandstanded about American jobs “lost forever to China” and Chinese leaders “manipulating” their currency.

Never mind that the evidence linking currency value to jobs is, er, slim at best. Even if the yuan doubled in value, Rickards points out a Chinese furniture maker would be making $236 a month — and a furniture maker in North Carolina still wouldn’t be competitive.

If we still had a gold standard — or even the Bretton Woods system in place between 1944-71, such yawning trade gaps would be impossible. The flows of gold between creditor and debtor nations would, naturally, maintain an equilibrium.

Meanwhile, manipulation is a two-way street: “China’s policy of pegging the yuan to the dollar,” Rickards writes, “was based on the mistaken belief and misplaced hope that the Fed would not abuse its money printing privileges.”

Fool me once…

“Given the choice,” Rickards writes, “between uncontrolled inflation with unforeseen consequences and a controlled revaluation of the yuan, the Chinese moved steadily in the direction of revaluation beginning in June 2010, increasing dramatically by mid-2011.”

You can see the result in the chart nearby. Through mid-2010, it took 6.8 yuan to equal one U.S. dollar. But with the conscious decision to strengthen the Chinese currency, it now takes barely 6.1 yuan to equal a dollar.

Thus, “the United States had won round one of the currency wars.” There will be more to come.

Regards,

Addison Wiggin

for The Daily Reckoning

Ed. Note: In The Daily Reckoning email edition — in which this piece was prominently featured — we offered subscribers a specific way to play these currency wars. If you’re not yet receiving the DR email, you’re missing out. Click here to sign up for free and get The Daily Reckoning delivered straight to your inbox every day around 4 p.m.

Comments: