A Caveman's Account of "Civilized Society"

Emblazoned across the lucre-basted exterior of the Internal Revenue Service Building in Washington, D.C., is one of the most intellectually polluted quotes any free mind is ever likely to encounter:

“Taxes are what we pay for a civilized society.”

Its effortlessly officious author, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., could scarcely have been more wrong in his (albeit paraphrased) assertion. Unless, that is, the mustachioed Rooseveltian meant to define “civilized society” as an arrangement that favors and promotes rule by brute force and violence, rather than one of free and voluntary association.

If, indeed, that was Justice Holmes’ idea of “civilized,” we shudder to think what he regards as uncivilized. But shudder we will…

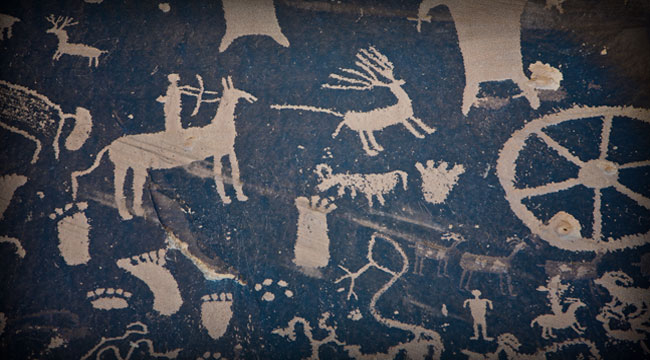

Let us consider, by way of illustration, the concept of the caveman, that apocryphal amalgam of prehistoric humans so often used to epitomize the unwashed, uncivilized elements of mankind’s past. To what does this boorish troglodyte resort when it comes to resolving complex matters of dispute? What is his go-to instrument for dealing with the problem posed by, say, the natural scarcity of goods? With what tool does he arbitrate over issues involving titles, rights, and claims?

Like Justice Holmes, Capt. Caveman’s preferred instrument of justice is… a club. Force, in other words. “It’s my way… or (insert oafish, baboonlike noises here) me club you to death.”

There is no opt-out here. No choice. And therefore, it must be said, no freedom. As the author Salman Rushdie (a man who has spent a good deal of his life under threat of force and violence from a particularly hysterical clutch of our fellow primates) once remarked, “Freedom to reject is the only freedom.”

Justice Holmes may have liked paying taxes. (He may have liked being flogged with a club, too. Who are we to say?) But by mandating that others do likewise, by employing the force of the state to ensure that they do, by denying them the freedom to reject the state’s claim on their property and to defend themselves against it, he is wielding the club — dangerously disguised as a gavel — of a decidedly uncivilized version of “justice.”

There are, of course, those questionless minds among us who take false refuge in such meaningless platitudes as, “But… but… but it’s the law!” To which we reply, “What kind of law is yours that seeks to endorse violence, rather than to protect us from it?”

“The purpose of the law,” observed classical liberal theorist Frederic Bastiat, “is to prevent injustice from reigning.” It is not to cause justice, in other words, but to shield us from its opposing force. And how are we to know when a law has fallen into the service of evil? The Frenchman offers this simple litmus test:

“See if the law take from some persons what belongs to them, and gives it to other persons to whom it does not belong. See if the law benefits one citizen at the expense of another by doing what that citizen himself cannot do without committing a crime.”

And if we find the state of affairs to be as such? Bastiat urges us to “abolish this law without delay, for it is not only an evil itself, but also it is a fertile source for further evils because it invites reprisals.”

For Holmes and his wretched ilk, the difference between “them” and “us,” between savage and civilized, is not to be found in the distance between war and peace, between force and voluntarism, between slavery and freedom. His is a civilization measured in degrees according to the size and efficacy of the agent of force… and the sickening pleasure its beggarly subjects derive in forever dwelling on the harsh receiving end of it.

Of course, the liberty-minded recognize immediately, almost instinctively, that no amount of initiated force is ever tolerable in a truly just and civilized society. Indeed, this is the core tenet of the nonaggression principle. Writes noted free market economist Walter Block on the subject:

“The nonaggression axiom is the lynchpin of the philosophy of libertarianism. It states, simply, that it shall be legal for anyone to do anything he wants, provided only that he not initiate (or threaten) violence against the person or legitimately owned property of another.”

In stark contrast to this fundamental bedrock of freedom, Justice Holmes not only implicitly advocates the use of force… but explicitly revels in it as a kind of privilege for which to be eternally thankful.

Wherever this core principle is endorsed, it betrays in its proponents a profound disgust for the human species, a disgust so visceral that it compels, urges, lusts even, for their ownership over and enslavement of others… all for the slaves’ own good, of course.

The impulse to own and to be owned is rooted in a foul and reprehensible sociopathy, one forged from a deep self-loathing, at once slavish and brutal. As such, it stands in special need of constant and public denunciation, of fierce, unapologetic, and uncompromising resistance by all who strive to further the cause of liberty.

Joel Bowman

Original article posted on Laissez Faire Today

Comments: