Sir, You’re Behind on Your Cheese

One free weekend last May, Pam, Micah, and I decided to take a ride to Bologna, in Emilia-Romagna, a mere three hours by car from our home in Il Piemonte.

Friends had told me that Bolognese cuisine is beyond compare, but I wasn’t all that excited. Yes, I love Parmigiano Reggiano, Grana Padana (another hard cheese), and balsamic vinegar, all from that part of Italy.

But Bologna is also home to the oldest continuously running university in the Western world, which makes it not only the place where the great Umberto Eco used to teach, but also a seething, filthy hive of communism.

Luckily, school was already out, so the kids who pay neither taxes nor tuition left the city to us.

There, we may have eaten the most memorable meal since we moved to Italy. In La Taverna Dei Peccati (The Tavern of Sins), the food was indeed sinfully good.

My tartare di chianina, the raw meat of a Tuscan cow, was out of this world. Pam’s Bolognese pork, which, somehow, included no dripping fat – a feat I still can’t get my head around – was the lightest, tastiest pork dish I’ve ever sampled. Micah devoured the spaghetti carbonara, which was better than any carbonara I’ve eaten anywhere else on Gaia’s green earth. The tiramisu was creamy beyond compare. Ok, people may have a point about Bologna being Italy’s culinary capital (though I still think Piemontese wine is the best).

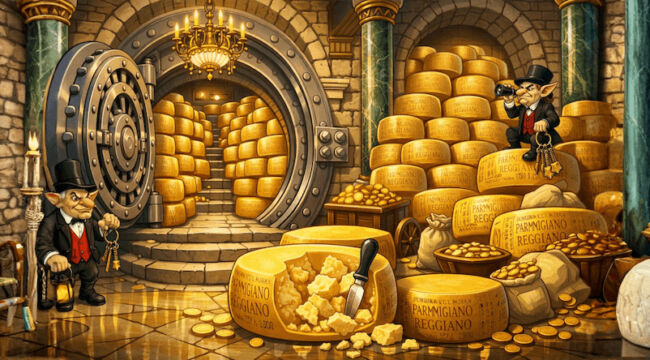

So I wasn’t surprised that in Emilia-Romagna, there’s a bank vault filled with something that would make a modern investment committee blink. It isn’t structured credit, venture capital, or sovereign bonds. It’s wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano.

This isn’t a stunt. For decades, Credito Emiliano (Credem) has been making loans backed by aging Parmigiano Reggiano, and the structure is a cleaner example of asset-based lending than much of what passes for sophistication in global finance.

A Pantry Dressed Up as a Bank Vault

In Emilia-Romagna, Parmigiano Reggiano is more than Italian cuisine. It’s a regulated industrial product with export demand, brand protection, and a well-understood production cycle.

Cheese must age 18 to 36 months before reaching peak quality and price. During that period, capital is tied up in inventory sitting on wooden shelves, slowly transforming from milk into a higher-value product.

However, the costs always arrive immediately. Farmers pay for milk, labor, energy, and equipment on an ongoing basis, while revenue doesn’t come in for years. Without financing, producers would be forced to sell younger cheese at lower prices or rely on costly, unsecured credit.

Turning Inventory Into Collateral

Credem’s solution is to treat aging wheels as what they really are: durable, traceable, marketable collateral.

A producer seeking a loan undergoes a standard review of their financial history, production capacity, and compliance with strict PDO rules. “Parmigiano Reggiano” is registered as a Protected Designation of Origin under EU quality schemes. Only cheese meeting the product specification can use this name.

The difference is in what secures the loan. Instead of real estate or machinery, the producer pledges specific wheels of cheese. Each wheel carries markings that certify origin and production date, making identification and tracking straightforward.

Once pledged, the cheese moves under the bank’s control into dedicated warehouses, called I Magazzini Generali delle Tagliate (The General Warehouses of Cuts). These facilities are climate-controlled and run by staff who understand cheese. The wheels are logged, monitored, and periodically inspected.

The Loan Term Mirrors the Aging Process

Loan-to-value ratios are conservative. They range from 70% to 80% of the cheese’s assessed value. Loan maturities match the aging timeline. By the time repayment is due, the cheese is close to peak market price.

The structure reflects a basic economic truth: some assets become more valuable with time, provided they are handled correctly. The loan bridges the cash gap between acquiring raw materials and selling the finished product.

Risk Management in the Warehouse, Not Excel

The operational side is where the real risk management sits. In the bank’s warehouses, temperature and humidity are tightly controlled, and specialists inspect the wheels, tapping them to detect defects. Spoilage rates under bank storage are far lower than in typical producer facilities.

While the cheese sits on the balance sheet, it’s also being protected and professionally managed. The bank’s control over storage reduces uncertainty about quality and preserves value in a way that paperwork alone cannot.

What Financing Changes for Producers

For cheese producers, the effect is immediate, welcome relief. They receive capital to run operations, pay staff, and invest in equipment, while still retaining upside exposure to fully matured cheese. The loan bridges the “cash gap” in operating work capital across the long production cycle.

The cheese remains in inventory but also serves as a financial asset that supports working capital. The producer isn’t forced to choose between survival today and better pricing tomorrow.

If a Borrower Can’t Repay

Should a borrower default, the loan’s resolution is straightforward. The bank already possesses the wheels of cheese, which are typically aged and prepared for market. Thanks to conservative loan-to-value ratios and consistent demand for authentic Parmigiano Reggiano, the bank has a high rate of debt recovery.

Once costs and the loan claim are satisfied, any remaining value is handled in accordance with the legal agreement. There is no complex repossession process because the collateral has been under bank control from the start.

Limited Complexity

This system is fabulously simple. Protection comes from over-collateralization, storage control, ongoing inspections, and deep knowledge of the local industry. There is no heavy reliance on derivatives to offset price risk, and Parmigiano Reggiano lending represents only a small portion of the bank’s overall business.

Even a severe shock to cheese prices wouldn’t threaten the institution as a whole.

Wrap Up

The broader lesson is more about alignment than cheese. The lending structure fits the physical and economic realities of the cheese industry. The bank understands the cheese’s production cycle, market, and its risks.

Instead of forcing a standardized credit model onto a specialized business, it builds the credit model around the business. In a financial system where collateral often consists of financial claims piled on top of other financial claims, a vault full of aging Parmigiano Reggiano is a reminder that lending can still be grounded in tangible goods, clear processes, and markets people genuinely use.

The result is a credit relationship built on something that exists outside screens and models. In practice, that makes it unusually resilient.

Comments: