“I Fear for Our Nation”

Are we going to be reliving the 1970s? Perhaps we will experience the stagflation of the 1970s in this decade, as financial excesses are worked out and monumental investments to retool our industrial base and infrastructure place a drag on productivity and profits. There is substantial logic in that scenario.

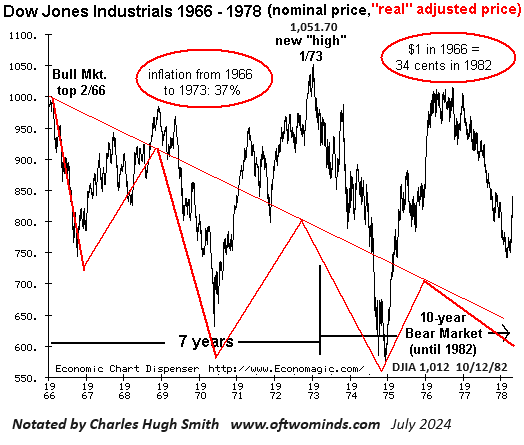

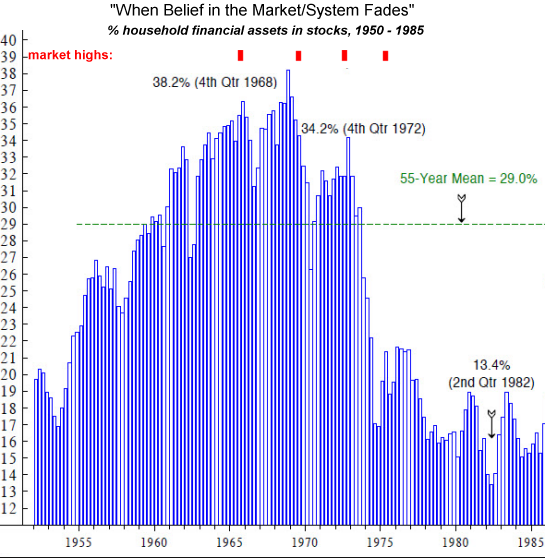

As the charts below illustrate, stagflation also crushed the stock market’s speculative dynamic. In the financial realm, That ’70s Show was characterized by a massive devaluation of the purchasing power of stocks as a result of elevated inflation and an equally massive decay in the speculative impulse to play the stock market, as the percentage of household assets in the stock market fell from 38% to 14%.

But what we might experience in addition to stagflation is something few seem to recall about the 1970s: the extraordinary unpredictability of events and crises. Consider the situation in April 1973, at the start of President Nixon’s second term.

Inflation had flared up, a currency crisis loomed and Nixon had issued sweeping policy changes in August 1971 ending the convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold in international markets and imposing wage and price controls.

The general outlook in early 1973 was positive, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) topped 1,000 again, reaching a new nominal high.

Who Could Have Known?

If any seer predicted the oil embargo/gas crisis that pushed Americans into long lines around gas stations in October 1973, or the Watergate cover-up leading to Nixon’s resignation in August 1974 or the attempt on President Ford’s life in September 1975, they’re unknown to the world.

If anyone predicted a decade of anti-establishment domestic terrorism, their prediction is lost to history. The hundreds of bombings of corporate America buildings, banks and other symbolic fortresses of the establishment have been ably documented in the book Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence.

If anyone predicted that the U.S. dollar would lose two-thirds of its purchasing power from 1966 to December 1981, their prediction isn’t well known.

What $1 bought at the market peak in 1966 cost $3 by December 1981, in the throes of the deepest recession since the Great Depression, a recession triggered by soaring interest rates and monetary tightening to crush the wage price spiral inflation that had become embedded in the economy by 1980.

Note that Dow 1,000 in October 1982 was only Dow 330 when adjusted for inflation since the peak in 1966 – $1 in February 1966 equaled $3.07 in October 1982.

From the Dow’s top in January 1973 at 1,051.70 to the point when the Dow reached 1,012 in October 1982, $1 in January 1973 was $2.31 in October 1982.

So Dow 1,000 in January 1973 meant Dow 435 in October 1982. These data points are from the CPI Inflation Calculator (BLS.gov).

Phantom Wealth

Few predicted the demise of the belief that “stocks only go up” and the market was a moneymaking machine available to all gamblers, oops, I mean “investors.”

Twisters on the Horizon

If we propose that the 2020s will mirror the 1970s not in the precise dynamics but in the unpredictability of crises and reversals of all that is stable, known and reliable, then we cannot possibly predict what lies ahead.

We can only anticipate twisters on the horizon that will be completely unexpected and potentially disruptive on a scale that stretches across culture, society, politics and the economy.

If we’re in a remake of That ’70s Show, the plot twists — and twisters heading our way — may be far wilder than we can currently imagine. And frankly, I fear for our nation.

That’s right — I fear for our nation, and I am not alone. The echoes of the past are becoming louder, and I recall the decades between 1961 and 1981 with trepidation, for that era was marked by crisis, tumult, discord, civil violence, war, a near miss of nuclear war, extreme polarization and assassinations.

Many Americans sense the country never really recovered from the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, or from the assassinations of presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. five years later in 1968.

An attempt on the life of President Gerald Ford was narrowly thwarted in 1975, and an attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan very nearly succeeded in 1981.

A terrible madness swept the land, as dozens of bombings and the bizarre kidnapping of media heiress Patty Hearst by a domestic terror cell pockmarked the 1970s, a decade marked by a failed presidency, revelations of domestic spying by federal security agencies and runaway inflation.

It was a very long night before morning dawned in America again. From the longer view, the 20 years of tumult can be understood as the political and social reaction to what changed in America in the previous 20 years of 1941–1960.

Look to the ’40s and ’50s

America had been roused from isolationism to fight a world war, forced to protect allies in Europe and Asia from the threat posed by an expansionist totalitarian Soviet Union and deal with a century-old reckoning with the racial divide that made a mockery of our nation’s principle that “all men are created equal” and should be treated equally before the law.

The promises made by the founding documents of the nation had yet to be fulfilled.

The very success of our protection of war-devastated allies created an economic crisis of our own, as the old, less-efficient industrial plant of America was outpaced by the new industries that arose in Germany and Japan with modern technologies, industries aided by America’s open door to exports and the strong dollar.

The 1970s was a decade of economic adjustment with high costs to both capital and labor as the energy crisis and the need to tackle industrial pollution drove a multitrillion-dollar (in today’s dollars) rebuilding of American industry, a process punctuated by recessions that caused great misery for those laid off and struggling with high inflation.

These sacrifices and conflicts eventually paid dividends. Inequality eased, high interest rates crushed the inflationary spiral and the investments in higher efficiencies and new technologies started paying off.

Another 20 Years of Chaos?

My fear is that we’ve entered another 20 years of tumult, chaotic conflict, infectious madness and discord, but without the resilience we possessed in the 1960s and 1970s, the resilience generated by low debt, strong domestic industries and supply chains, low levels of regulation, low-cost health care and education and much higher levels of civic virtue, community, national purpose, moral legitimacy and self-reliance than are visible today.

Whether we admit it or not, we are riven by rising inequality in wealth and opportunity, high debt loads and little consensus on how to get through the night in one piece and emerge better from facing the challenges head on.

I fear the siren-song appeal of denial and magical thinking, as if a rocket to Mars or a new phone app or another AI chatbot will fix what’s broken in America.

I fear our buffers have been thinned, and our ability to make sacrifices for the future has been lost. Our moral foundations are in such tatters that getting rich by whatever means are within reach is now the “solution” to the coming storm, as if greed bled dry of ethics isn’t a proximate cause of the coming storm.

My hope is that we gain the wisdom to see there are no easy solutions, no one-size-fits-all fixes, that solutions will be localized, partial, contingent on continual adaptation to changing conditions and that this continual experimentation and evolution requires an acceptance of continual failures and a keen sense of humility about our limits.

I hope we gain the wisdom that we need each other, not as enemies but as colleagues, not always in agreement but respectful nonetheless.

I’m hopeful, but I’m not necessarily confident.

Comments: