The Polycrisis

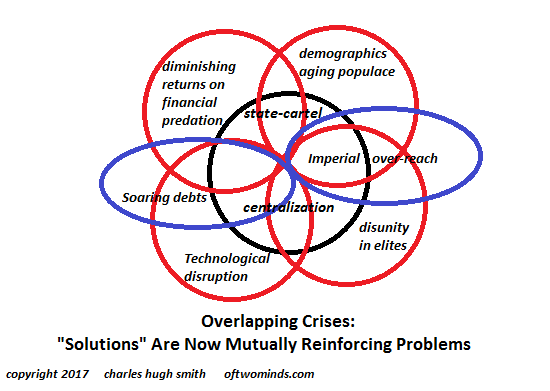

Back in 2017 when I composed this graphic of overlapping crises, the word polycrisis was not yet in common use. Polycrisis has various definitions, for example: “the simultaneous occurrence of several catastrophic events.”

But this doesn’t explain the truly dangerous dynamic in polycrisis, which is the nonlinear, mutually reinforcing potential of disparate crises to generate effects much larger than the initial causes. This definition is closer to the mark: “Many different problems happening at the same time so that they together have a very big effect.”

Put another way: 1 + 1 + 1 doesn’t generate an effect of 3, it generates an effect of 9.

You’ll notice the crises on my graphic are internal socioeconomic dynamics: state-cartel centralization, demographics, soaring debts, Imperial overreach, technological disruption, disunity in elites and diminishing returns on financial predation.

Many don’t see these as crises; they’re seen as factors, not as potentially catastrophic dynamics. This is the linear analysis: None of these dynamics is actually threatening to the stability of the U.S.

The nonlinear analysis is: Considering each one as a discrete dynamic, that’s true. But these are mutually reinforcing crises because the status quo “solutions” to each one become mutually reinforcing problems which generate much larger effects than most believe possible.

Note that external factors such as war and climate change are not shown. These conditions are not entirely controllable by U.S. policy decisions. They affect the entire world, not just one nation-state. That said, external crises add additional nonlinear influences to the polycrisis.

Polycrisis and Supply and Demand

The human mind is not particularly well-adapted to polycrisis: We struggle to adapt to the drought, then the earthquake knocks down the village walls, then the tsunami pounds what was left, followed by the epic flooding, then the hurricane batters the survivors, who witness the volcano erupting and wonder what they did to anger the gods and goddesses so mightily.

Now, not all polycrises are equal, and it’s worth noting the different types of crises, and how the “solutions” can turn the crisis from controllable to uncontrollable. One way to understand crises is supply and demand: If there are supplies on hand and the problem is a lack of money to pay for the supplies, governments can print or borrow the money to ease the crisis.

In other cases, a scarcity of supply can be ameliorated by drawing upon reserves that were set aside for just such a shortage.

But if there’s insufficient supply and no substitutes or reserves, the crisis can quickly overwhelm the system. Consider fresh water. A short-term drought can be managed by tapping water stored in dams or drilling deeper wells.

But once the drought becomes long-term, there are no longer any reserves or substitutes available. Water is heavy and costly to transport, and it’s not feasible to import it from other countries.

Once borrowing or printing more money can’t solve the problem, or becomes the problem, the wheels fall off. We’ve lost the ability to solve any problems that can’t be resolved painlessly and without elites and incumbents making any sacrifices.

Printing or borrowing money can’t solve the problem. The entire edifice of the market economy is based on the assumption that there’s always a substitute available if there’s enough money to buy it. Markets no longer function when there are no substitutes, as the wealthy will buy up whatever is available and everyone else will do without.

No Market Solution to Moral Decay

What’s the market solution to moral decay and the decline of civic virtue? There isn’t one. Markets assume price will be discovered by supply and demand, and so corruption becomes a “market” of bribes and favors, an auction that “works” as a market even as it undermines civil society.

The sacrifice-free “solutions” approved by the self-serving status quo elites end up generating self-reinforcing dynamics that generate new crises. Borrowing or printing money is every elites’ favorite “solution.” But if “free money” doesn’t solve the crisis in short order, the excess of “free money” becomes its own problem.

In other words, doing more of what’s failed because that’s what worked in the past becomes a self-reinforcing crisis as the elites cling to whatever is easiest and demands the least sacrifices.

Put another way: The system is broken beneath the surface, but these structural failures only become visible when they reinforce each other in a polycrisis. Elites and institutions have grab bags of “solutions” based on prior crises, grab bags which are inadequate when new, mutually reinforcing crises emerge.

But since they’re constrained by what’s acceptable to elites, interest groups and incumbents, their “solutions” are limited to “safe” responses that don’t demand any sacrifices of elites, interest groups and incumbents. These policy tweaks are simply too limited to address the problem, and so they exacerbate the problem rather than solve it.

Nobody in a position of responsibility believes the systems we depend on can unravel. This belief in the permanence of systems that are actually inherently fragile cripples those in charge, as their crisis responses are completely inadequate to the scale of the effects generated by mutually reinforcing crises.

The erosion of accountability doesn’t seem to matter now, but it will matter when things start unraveling. Everyone will have an excuse, call another emergency meeting and demand that somebody somewhere else do something to make the pain stop.

But the decay of accountability is consequential, and there won’t be anyone available to “save the day” because those who demanded accountability of others have been cashiered or sent to bureaucratic Siberia.

When Time Runs Out

Everyone believes they’ll have plenty of time to craft a response, but time is what becomes scarce in rapidly delaminating nonlinear crises. We’re prepared for discrete events that occurred in the recent past, but not for self-reinforcing/mutually reinforcing dynamics.

The system is designed to handle one challenge at a time, but not a long-term multiplicity of challenges.

And as noted above, the status quo is unaware of its own systemic flaws because sclerosis and corruption are all anyone has known. A broken system can still function when the demands placed on it are modest. But when things get serious, the system breaks down, and everyone who ignored or denied the structural weaknesses is caught off guard.

Not all polycrises are equal. Those that can be resolved by borrowing or printing money are controllable, at least until the expansion of “free money” itself becomes a self-reinforcing crisis.

But problems that can’t be resolved painlessly with more “free money” — systemic sclerosis and corruption, moral decay, warring elites, demographic decline, diminishing returns on financial predation, state-cartel strangleholds on the economy, supply scarcities for which there are no substitutes — have the potential to reinforce one another to the point the system’s structural rot becomes visible.

By then, it’s too late.

How could this be happening? Indeed. How could this be happening? That’s the difficulty with nonlinear, mutually reinforcing crises: Our overconfidence, hubris and refusal to consider sacrifices will be our undoing.

Like what you’ve read? Go here for more.

Comments: