“Are You 100% American? Prove It!”

I hope you’re having a good Memorial Day long weekend. Meanwhile, how do you like the title of this article? Did it catch your attention? Because the idea is to question your patriotism if you don’t fork your money over to the U.S. government.

It’s abrupt, but don’t blame me! That wording isn’t mine. Our government said this, in a poster from 1918 during the Third Liberty Loan drive that raised money to fight World War I. Here it is, courtesy of the National Archives:

Buy Bonds! (Or we’ll question your patriotism.)

This patriotism-questioning, guilt-trip advertising reflects the level of desperation within the U.S. government in 1917-18, all to raise funds to fight a war. And it’s worth recalling for two reasons.

First, we’ll discuss World War I and the Liberty Bond campaign because it’s Memorial Day weekend, when we remember America’s fallen from past wars.

And second, we’ll discuss government debt. Because right now the U.S. government is in the midst of a political battle over raising the ceiling on that national debt.

That is, the Democrat-run White House and Republican-majority House of Representatives are squabbling over how to continue to fund the government via the sale of… yes… bonds. Lots of bonds. Much like what happened back during World War I. Only with lots more zeroes.

One intriguing bit of history in all this — still pertinent! — is that the idea of a ceiling on national debt originated during World War I. It was part of legislation that enabled the second (of four) Liberty Bond drives which raised the cash that paid for the war.

So in this article we’ll discuss bonds, money and war. And rest assured, this history from 100-plus years ago remains relevant.

Where to start? OK, how about with the second term of President Woodrow Wilson.

In 1916, the former professor from Princeton campaigned for reelection on the slogan that “He Kept Us Out of War,” meaning Wilson kept the U.S. out of the then-raging war in Europe.

But you know what happened, right? Once Wilson was safely back in the White House, he took the martial plunge.

Wilson was reinaugurated as president on March 4, 1917, and less than a month later, on April 2, he asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany. The cassus belli was German submarine warfare, namely attacks on U.S. ships that carried war materiel to Britain and France.

Well, wars are expensive: “War costs much silver,” wrote Sun Tzu in his ancient text on strategy.

To join the fight in Europe, the U.S. government had to raise immense sums of money. More money, in fact, than the U.S. Treasury had ever raised before in a very short time. And how does one do that? One way is to sell bonds, and in ways and amounts never seen.

That is, neither the U.S. government nor general economy was geared for the sale of massive levels of bonds, let alone war bonds. Yes, per the Constitution the federal government could issue debt, but the history along those lines was quite modest.

From the earliest days of the Republic, when the federal government needed funds, it issued bonds. And with every raise from 1789 to 1917, the amount and accompanying interest rate was authorized by Congress. Up until 1917, federal law provided nothing like a debt ceiling.

Then along came Woodrow Wilson, and with U.S. entry into the European war fundraising began immediately…

Read on to learn how Wilson’s destructive policies led us to where we are today.

It All Starts With Wilson

By Byron King

On April 24, 1917 — about three weeks after the declaration of war — Congress passed the First Liberty Loan Act; $5 billion raised via 30-year bonds paying 3.5%.

That was just the beginning of a Niagara-level of military spending. As you can imagine, the war, and of course the Treasury, needed more.

So on October 1, 1917 Congress passed the Second Liberty Loan Act; $3.8 billion of 25-year bonds paying 4%. And along with authorization to raise funds via bonds in this legislation, Congress set a ceiling of $15 billion of overall government indebtedness, the first debt ceiling in U.S. history.

Here’s what happened. Legislators who enacted this new, statutory limit on borrowing were shocked at the rapid growth of federal obligations. Wilson’s war took government spending to unheard-of levels, with entirely unknown future effects on the national economy.

The Explosion of Debt

For perspective, in the years immediately preceding U.S. entry into the war, the annual federal budget was under $1 billion. Yet as 1917 unfolded, federal debt expanded by an order of magnitude, from under a billion to well over ten billion dollars!

War or no, Congress included at least a few members with a flinty, banker-like view towards exploding levels of debt. Indeed, back then, everyone alive had come of age in a nation that routinely used hard money as currency, namely gold and silver.

From the Civil War to 1900, the U.S. followed a monetary policy of bimetallism, meaning that silver and gold defined the national currency at fixed ratios. Then in 1900, President McKinley signed the Gold Standard Act, which placed the U.S. squarely on the side of gold as the definition of American money.

But on December 23, 1913, President Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act which established a U.S. central bank. The idea was for this new entity to issue currency by fiat, meaning book entries of money unbacked by ounces of gold or silver. In other words, the Fed gave the U.S. what people called an “elastic” currency.

The idea of elasticity to money supply meant that the central bank could expand or contract the amounts of currency in circulation to meet the needs of the country’s business cycles. If there was an agricultural crash in one place, or an industrial crash somewhere else, the banking system would be able to function with loans or another financial backstop from the Fed.

The Floodgates Open

As fate would have it though, in 1914 the first major challenge to the newly created Federal Reserve was to finance a global war that began in August of that year, “the Great War” as it was called, now known as World War I.

By the end of 1914 and into 1915 the Fed was rapidly expanding the money supply. It issued billions of dollars in new credit to support massive growth of trade in war-related materials and machinery, moving from the U.S. to France and Britain.

It would be a stretch to say that anyone at the time really saw what was coming. Nobody has that kind of crystal ball.

But as events unfolded the earliest, formative days of the Fed brought an explosion of money creation. And not classical, gold standard money; no, it was fiat and mere bookkeeping entries from the Fed to banks that then issued letters of credit to pay for wartime goods and services. It was an unprecedented way to make vast claims on real wealth.

And this brings us back to that debt ceiling law in 1917, part of the Second Liberty Loan legislation.

In essence, a few members of Congress applied their quaint notions of hard money to the new cascade of spending and debt. They created a debt ceiling as part of national law because they wanted at least a semblance of legislative control over federal outlays, and certainly outlays financed by issuance of wartime bond-debt.

The “Sword of Preparedness”

In 1918 the U.S. passed two more Liberty Loan acts as the war unfolded, in April and September; these raised a total of $11 billion in 10-year bonds at between 4.15 and 4.25%. And then the First World War ended, on November 11, 1918.

Through it all, the federal government enlisted celebrities to travel across the nation, to urge people to buy bonds. For example, movie stars like Mary Pickford and a young Charlie Chaplin gave talks to promote the bonds. And even the Boy Scouts got into the act, urging fellow Americans to support the effort.

Boy Scout hands “Sword of Preparedness,” to Lady Liberty; National Archives.

After the war concluded, the U.S. still needed vast sums of money to pay ongoing obligations and raised another $4.5 billion via what were called “Victory Loan” bonds; 4-year term at 4.75%, payable in gold, no less.

All in all, U.S. government’s war indebtedness topped-out in August 1919 at just over $25.5 billion, comprised of Liberty Bonds, Victory Notes, War Savings Certificates, and various other government securities. And the next question was how to pay down these obligations.

Indeed, the peacetime question of how to repay the country’s wartime debt came home with a vengeance in the wake of a massive recession (some say depression) in 1920-21. Where was the wealth, let alone the tax mechanism for the government to raise funds and pay down such immense debt?

The Role of Prohibition

Another intriguing, if not astonishing angle to this looming lack of tax revenue was the 18th Amendment which came into effect in January 1919 and led to the era of Prohibition, via a ban on the sale of alcoholic drink.

In turn, this led to a massive loss of formerly large and predictable tax revenue flows to both the federal fisc as well as in most states. Plus, Prohibition put many firms out of business and led to job losses for hundreds of thousands of workers across the land, from winemakers, brewers and distillers, to farmers, barrel-makers, drivers, saloonkeepers and many more. Financially, banning booze was a national disaster.

In Washington, D.C. of the 1920s, under Presidents Harding and Coolidge, and with no less than the formidable Andrew Mellon as Secretary of Treasury, it was apparent that the war bonds would not be paid in full within the scheduled life of 4-year, 10-year and even 25- and 30-years.

Liberty Loans and the Crash of ‘29

Getting back to the Liberty Loans for the war, and to make a long story short, the solution was simply to roll them over at maturity, to issue new bonds for old. And it worked throughout the 1920s, until the Crash of 1929 and then the Great Depression came along and upended the entire edifice of federal finance.

In 1933 Franklin Roosevelt became President. Almost immediately after taking office, he “called in” the nation’s gold and then revalued it. And then came government repudiation of elements in wartime bonds that referred to repayment in gold. The matter was resolved via the Gold Clause cases that went before the Supreme Court, which took the government off the hook.

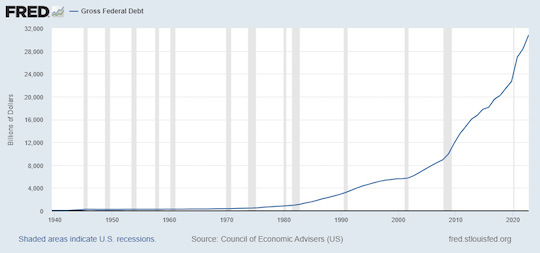

Which brings us to the past eight decades of government debt, now growing in a manner that looks hyperbolic, if you believe the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis:

U.S. federal debt, unadjusted for inflation. Courtesy Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

This FRED chart goes back to 1939, the oldest reliable data, apparently. You can extrapolate backwards and discern that federal debt in the 1920s and 30s was actually rather small beer, so to speak. Meaning that the big debt rollup began in the 1970s, into the 80s, 90s and then since 2000 it’s up, up and away.

Which brings us to the present, and the current political battle over raising the debt ceiling to conform with the underlying requirements of that Second Liberty Loan act of 1917.

Billions vs. Trillions

During World War I, people worried over raising a few billion dollars; today, the fight is over trillions, with more to come. The goal is for Uncle Sam to continue to spend far more than he takes in every year. We’re looking at a runup of national debt from $31-something trillion up to about $33 trillion, give or take, in just the next nine months or so.

And if the debt ceiling doesn’t change, then the U.S. Treasury cannot legally borrow more money, and the stock market will crash, and all hell will break loose. Or so they say.

Well, we’ll see. No doubt, the politicians will do something. After all, they want their paychecks next week, too, the same as everybody else.

But as it all unfolds, think back to World War I, Woodrow Wilson, the use of patriotism as a club to beat people into giving their gold-backed money to the government, all to fight a war on another continent. And we’re still doing it.

Well… like I said, happy Memorial Day long weekend.

Comments: