“A Bucket of Cold Water in the Face”

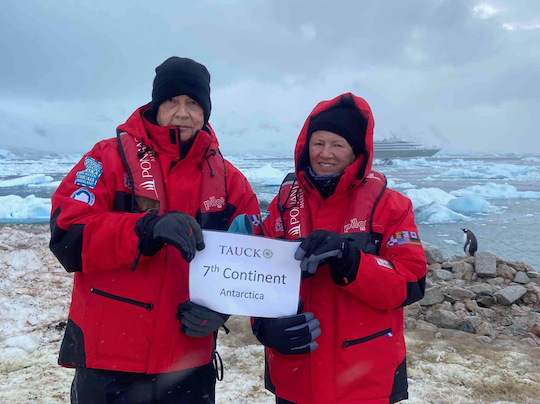

I’m currently exploring Antarctica, faraway from all the world’s turmoil.

My expedition just doesn’t want to end up like the people on the Titanic! This iceberg was a bit too close for comfort:

But this isn’t a travelogue and you want to know what’s happening in the fields of finance, economics, politics, geopolitics and more. So let’s dig in…

I’ve been writing a lot lately about topics such as U.S. politics, the Federal Reserve, the situation in Ukraine and even the threat of nuclear war. But today I want to address the biggest and most complex topic on the geopolitical landscape today — China.

China’s importance in global financial markets and geopolitics is undisputed. It has the world’s second-largest economy after the U.S. at $18.3 trillion in annual GDP, just under 20% of total global output. It has the world’s second-largest population after India, with about 1.4 billion people.

It has the world’s third-largest landmass after Russia and Canada with about 6.3% of the total dry land on Earth. It has the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal after Russia and the U.S. with 350 nuclear weapons (although that’s a distant third since Russia has 6,257 nuclear weapons and the U.S. has 5,550 such weapons).

By these and many other measures, China is one of the most powerful nations on Earth.

Meanwhile, China’s average annual economic growth rate over the past eight years is 10.55%. The compound growth rate over the same span is 123%. Put differently, the size of the Chinese economy more than doubled in eight years.

With growth like that, it’s a small wonder that global analysts confidently predicted that China would surpass the U.S. in total annual GDP by 2030, if not sooner. Other analysts said that just as the twentieth century was the American Century, the twenty-first century would be the Chinese Century.

Yet few of these predictions, if any, will likely come true.

Reality has hit China-watchers like a bucket of cold water in the face. Even the China boosters, affectionately if sarcastically called panda huggers, are waking up to the fact that China is a desperately poor country despite a long list of paper billionaires. A thirty-year hypnotic spell has been broken.

The more astute analysts always knew China would hit the wall economically in a bigger, more momentous version of what is known to economists as the middle-income trap. The numbers I cited above aren’t quite as impressive when you take a deeper look at them.

Since 2008, China’s average annual growth is 7.20%. That growth rate is 32% lower than the annual rate that prevailed from 2000 – 2007. The compound growth rate over the same span is 182%. That’s substantial, but 182% in fifteen years is not impressive compared to 123% in just eight years prior to 2008.

For an apples-to-apples comparison, compound growth over the last eight years was just 56%, less than half the compound growth rate of the eight years from 2000 to 2007.

This slowdown in recent years is striking with growth between 9.40% and 10.70% in the first four years (2008 – 2011) compared to growth of only 2.2% to 5.6% in the last four years (2019 – 2022).

Of course, Chinese data is routinely skewed to the upside. It is entirely likely that China’s economy actually shrank in 2022 and there is independent data available that suggests exactly that.

It’s not enough to blame this slowdown on the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic. China was barely affected by the global financial crisis and posted healthy growth of 9.65% in 2008.

The slowdown in Chinese growth, which will continue, is due to even larger forces than financial panic (2008) and pandemic (2020 – 2023).

What’s holding China back?

Comments: