Government: A "Social Contract" You Never Signed

[Ed. Note: The following is excerpted from Bill Bonner’s book Hormegeddon: How Too Much Of A Good Thing Leads To Disaster.]

People only understand the world by analogy. The deals and documents of a manufacturing, merchandising economy suggested an explanation for government — that it was a kind of ‘social contract.’ But a ‘social’ contract is to a real contract what an inflatable sex doll is to a real woman; it may be good enough in certain ways, but not the essential ones.

Government is an expression of power relationships, in which some people seek to dominate others by force. These dominators gather ‘insiders’ together so that they can take money, power and status away from other people, the ‘outsiders.’ That is not how contracts work.

If it were a contract, what kind of contract would it be? A services contract? Many people think that government provides some service. That is true, but it is incidental. Governments often deliver the mail. But they don’t have to. They would still be governments even if they didn’t control the Post Office. And what if they didn’t have a department of inland fisheries, or a program to promote self-esteem in obese tollbooth operators?

You can’t have a contract unless you have two willing and able parties…

They would still be in the government business. They would still have their helicopters, chauffeurs and expense accounts. But if they lost control of the police or the army, it would be an entirely different matter. Written “contracts” and constitutions are decorative details of government; force is the essence of it.

Andrew Jackson understood this all the way back in 1832 when he essentially told Chief Justice John Marshall to pound sand after the latter issued the Court’s opinion in Worcester v. Georgia. “John Marshall has made his decision,” Jackson is reported to have said, “Now let him enforce it.” Without armies and police, governments would no longer be governments.

At the end of the 19th century, people were asked what they thought the new century would bring. Almost universally they predicted that government would grow smaller. Why? Because people were becoming much richer and better educated. People who were rich and well-educated could solve their own problems and organize themselves to provide the services they wanted. The thinkers of the time thought there would be less need for government.

It didn’t turn out that way. Because the thinkers misunderstood what government really is. Government is not an organization that contractually provides benefits and services, and therefore shrinks as the need subsides. As a society grows richer it can afford more illusions, more entertainments, more redistribution of wealth, more regulation, higher taxes, and more unproductive people. The insiders take more, because there is more to take and because outsiders can afford more exploitation. Not surprisingly, governments grew tremendously in the 20th century.

The “social contract,” is a fraud. You can’t have a contract unless you have two willing and able parties. They must come together in a meeting of the minds — a real agreement about what they are going to do together.

There was never a meeting of the minds to establish a “social contract” with government. The deal was forced on the public. And now, imagine that you want out. Can you simply “break the contract?” Imagine refusing to pay your taxes or declining the services of the TSA and other government employees. How long before you wound up in jail? Ask Wesley Snipes; he can tell you.

What kind of contract is it that you don’t agree to and can’t get out of? Also, what kind of a contract allows for one party to unilaterally change the terms of the deal? Congress passes new laws almost every day. The bureaucracy issues new edicts. The tax system is changed. The pound of flesh they already got wasn’t enough; now they want a pound and a half!

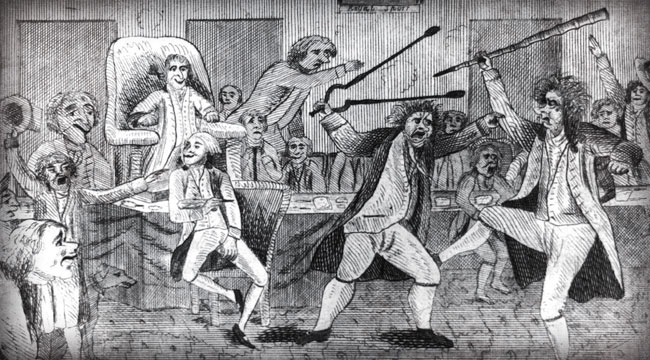

Insiders always use government to transfer power and money from the outsiders to themselves. When wealth was easy to identify and easy to control — that is, when it was mostly land — a few insiders could do a fairly good job of keeping it for themselves. The feudal hierarchy gave everybody a place in the system, with the insiders at the top of the heap. But come the Industrial Revolution and suddenly wealth was accumulating outside the feudal structure. Populations were growing too, and growing restless. The old regime tried to tax this new money, but the new ‘bourgeoisie’ resisted. It wanted to be an insider too.

“No taxation without representation!” The outsiders wanted in.

There never is one fixed group of people who are always insiders. Instead, the insider group has a porous membrane separating it from the rest of the population. Some people enter. Some are expelled. The group swells. And shrinks. Sometimes, a military defeat or a revolution brings a whole new group of insiders sweeping into power. Elections, if they happen, then change the make-up of that core group.

But the genius of modern representative government is that it cons the masses into believing that they are insiders too. They are encouraged to vote and to believe that their vote really matters. In some places the outsiders are required, by the insiders of course, to vote.

The common man likes to think he is running things. And he pays dearly for it. After the insiders brought him into the voting booth, his taxes soared. In America, with taxation without representation, before the war of independence, the average tax rate was as little as 3% or so. Now, with representation, government spends about a third of national income. And if you live in a high-tax jurisdiction, such as Baltimore, California or New York, you will find your state, local and federal tax bill run up to 50% or more of marginal income.

In short, the insiders pulled a fast one. They allowed the rubes to feel like they had a solemn responsibility to set the course of government. And while the fellow was dazzled by his own power…they picked his pocket!

It didn’t stop there. Under the kings and emperors, a soldier was a paid fighter. If he was lucky, his side would win and he’d get to loot and rape in a captured town for three days. Relatively few people were soldiers, however, because societies were not rich enough to afford large, standing armies.

A little government is probably a good thing… But the point of diminishing returns is reached quickly.

The industrial revolution changed that too. By the 20th century, developed countries could afford the cost of maintaining expensive military preparedness, even when there was not really very much to be prepared for. But the common man was skinned again. Not only was he expected to pay for it, still under the delusion that he was in charge, he also believed he had a patriotic duty to defend the insiders’ power by doing the work he was paying for! No wonder the modern democratic system has spread all over the world. It is the best scam in town. Nothing can compete with it.

In 1776, Adam Smith published his Wealth of Nations, arguing that commerce and production were the source of wealth. Government began to seem like an obstruction and a largely unnecessary cost. Its beneficial role was limited, said Smith, to enforcing contracts and protecting property. The school of laissez-faire economics maintained that government was a “necessary evil,” to be restrained as much as possible. The “government that governs best,” as Jefferson put it, “is the one that governs least.”

Government — according the Liberal philosophers of the 18th and 19th century — was supposed to get out of the way so that the ‘invisible hand’ would guide men to productive, fruitful lives. Smith thought the arm attached to the invisible hand was the arm of God. Others believed that not even God was necessary. Men, without central planning or God to guide them, would create a ‘spontaneous order’ which, guided by an infinite number of private insights, would be a lot nicer than the clunky one created by kings, dictators or popular assemblies.

The more government got in the way, the less useful it became. In other words, the more it became subject to the law of declining marginal utility. A little government is probably a good thing. The energy put into a system of public order, dispute resolution, and certain minimal public services may give a positive return on investment. But the point of diminishing returns is reached quickly.

Regards,

Bill Bonner

for The Daily Reckoning

Ed. Note: In today’s issue of The Daily Reckoning readers received exclusive commentary from Addison Wiggin and Bill. They also had a chance to grab a copy of Bill’s new book. Just a small part of being a reader of the FREE Daily Reckoning email edition. Click here to sign up right now and never miss another great opportunity like this.

This essay was excerpted from Bill Bonner’s book Hormegeddon: How Too Much Of A Good Thing Leads To Disaster.

Comments: