Fed Lets Circus Roll On

The Federal Reserve sat idle on its hands today.

And so the federal funds rate stays nailed to the floorboards. Monthly asset purchases will roll on at $120 billion the month.

Markets feared that Mr. Powell and mates might telegraph hawkish hints today as growth — and inflation — bubble and percolate.

But the reign of doves is extended yet again. Mr. Powell, today:

Following a moderation in the pace of the recovery, indicators of economic activity and employment have turned up recently, although the sectors most adversely affected by the pandemic remain weak. Inflation continues to run below 2 percent.

The majority of FOMC members divine no rate hikes until 2023.

Stocks were up and away on today’s news…

Music to the Market’s Ears

The Dow Jones closed trading above 30,000 for the first occasion today — at 30,015 in fact.

The S&P added 11 points; the Nasdaq 53.

And why wouldn’t the stock market take a leap today? Mr. Michael Arone, chief investment strategist with State Street Global Advisors:

[It] sounds like the perfect scenario for investors and the outlook and you’re seeing market response to this very optimistic view. Monetary policy is going to remain largely accommodative almost regardless of what happens with interest rates, inflation and asset prices.

And so the circus runs yet… until the tent crashes down.

Gold — meantime — gained $12 and change on Mr. Powell’s dovish mumblings.

The gyrations, transiences and effervescences of the daily scenery offer us grand amusement.

But they do not seize our interest. It is the eagle’s view, the overall view, the view sub specie aeternitatis that fascinates us.

That is the view we take today…

The Lowest Rates in 5,000 Years

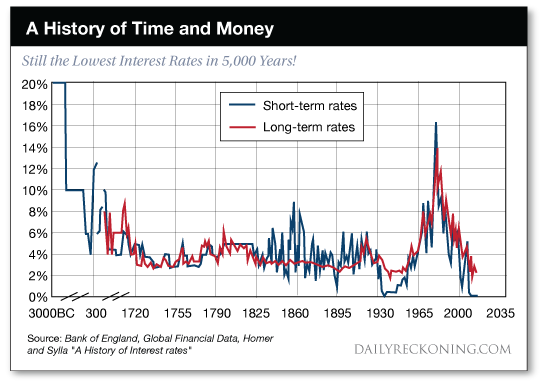

The chart below gives 5,000 years of interest rate history. Please direct your attention to anno Domini 1895.

Rates had never been lower — not in all of recorded history:

Rates would sink lower only on two subsequent occasions — the dark, depressed days of the early 1930s — and the present day, dark and depressed in its own way.

The Arc of the Universe Bends Toward Low Interest Rates

Paul Schmelzing professes economics at Harvard University. He is also a visiting scholar at the Bank of England.

He has conducted a strict inquiry into interest rates throughout history. From which:

The discussion of longer-term trends in real rates is often confined to the second half of the 20th century, identifying the high inflation period of the 1970s and early 1980s as an inflection point triggering a multi-decade fall in real rates. And indeed, in most economists’ eyes, considering interest rate dynamics over the 20th century horizon — or even over the last 150 years — the reversal during the last quarter of the 1900s at first appears decisive…

Here the good professor refers to “real rates.”

The real interest rate is the nominal rate minus inflation. Thus it penetrates the monetary illusion.

It exposes inflation’s false tricks — and the frauds who hold them up their shortsleeves.

In one word… it clarifies.

And the chart above reveals another capital fact…

The Long View

Revisit the chart. Now take an eraser in hand. Run it across the violent lurch of the mid-to-late 20th century.

You will come upon this arresting discovery:

Long-term interest rates have trended downward five centuries running. It is this, the long view, that Schmelzing takes:

Despite temporary stabilizations such as the period between 1550–1640, 1820–1850 or in fact 1950–1980 — global real rates have shown a persistent downward trend over the past five centuries…

This downward trend has persisted throughout the historical gold, silver, mixed bullion and fiat monetary regimes… and long preceded the emergence of modern central banks.

What is more, today’s low rates represent a mere “catch-up period” to historical trends:

This suggests that deeply entrenched trends are at work — the recent years are a mere “catch-up period”…

In this sense, the decline of real returns across a variety of different asset classes since the 1980s in fact represents merely a return to long-term historical trends. All of this suggests that the “secular stagnation” narrative, to the extent that it posits an aberration of longer-term dynamics over recent decades, appears fully misleading.

Is it true? Is the nearly vertical interest rate regime of the later 20th century a historical one-off… a chance peak rising sheer from an endless downslope?

What explains it?

Interest Rate Spikes, Explained

Galloping economic growth explains it, says Lance Roberts of Real Investment Advice.

He argues that periods of sharply rising interest rates are history’s lovely exceptions. Why lovely?

Higher interest rates are a function of strong, organic, economic growth that leads to a rising demand for capital over time.

In this view, rates went spiking at the dawn of the 20th century. It was, after all, a time of lightning industrialization and dizzying technological advance.

Likewise: The massive post-World War II rate spike owes directly to the economic expansion then taking wing. Roberts:

There have been two previous periods in history that have had the necessary ingredients to support rising interest rates. The first was during the turn of the previous century as the country became more accessible via railroads and automobiles, production ramped up for World War I and America began the shift from an agricultural to industrial economy.

The second period occurred post-World War II as America became the “last man standing”… It was here that America found its strongest run of economic growth in its history as the “boys of war” returned home to start rebuilding the countries that they had just destroyed.

Let the record show that rates peaked in 1981. Let it further show that rates have declined steadily ever since.

And so we wonder: Was the post-World War II period of dramatic and exceptional growth… itself the exception?

The Return to Normal

Let us widen our investigation by summoning an additional detective. For example, New York Times senior economic correspondent Neil Irwin:

Investors have often talked about the global economy since the crisis as reflecting a “new normal” of slow growth and low inflation. But just maybe, we have really returned to the old normal.

More:

Very low rates have often persisted for decades upon decades, pretty much whenever inflation is quiescent, as it is now… The real aberration looks like the 7.3 percent average experienced in the United States from 1970–2007.

That is precisely the case Schmelzing argues before the jury.

But at this point, we must hoist a red warning flag…

A Pursuit of the Wind

Drawing factual connections between historical eras can be a snare, a chasing after wild geese, a pursuit of the wind.

Success requires a sharpshooter’s eye… a surgeon’s hand… and an owl’s wisdom.

The aforesaid Schmelzing knew the pitfalls awaiting him before setting out. But he believes he has emerged from the maze, clutching the elusive grail of truth.

Today’s low rates are not the exceptions, he concludes in reminder. They represent a course correction, a return to the long, proper path.

How long will this downward trend continue, professor Schmelzing?

The Look Ahead

Whatever the precise dominant driver — simply extrapolating such long-term historical trends suggests that negative real rates will not just soon constitute a “new normal” — they will continue to fall constantly. By the late 2020s, global short-term real rates will have reached permanently negative territory. By the second half of this century, global long-term real rates will have followed…

But can the Federal Reserve throw its false weights upon the scales… and send rates tipping the other way?

With regards to policy, very low real rates can be expected to become a permanent and protracted monetary policy problem…

The long-term historical data suggests that, whatever the ultimate driver, or combination of drivers, the forces responsible have been indifferent to monetary or political regimes; they have kept exercising their pull on interest rate levels irrespective of the existence of central banks… or permanently higher public expenditures. They persisted in what amounted to early modern patrician plutocracies, as well as in modern democratic environments…

We have argued previously that central banks wield far less influence than commonly supposed.

Here we find validation.

But we are unconvinced rates are headed inexorably and unerringly down.

Tomorrow, another possible lesson — a warning — from the book of interest rates.

Regards,

Brian Maher

Managing Editor, The Daily Reckoning

Comments: